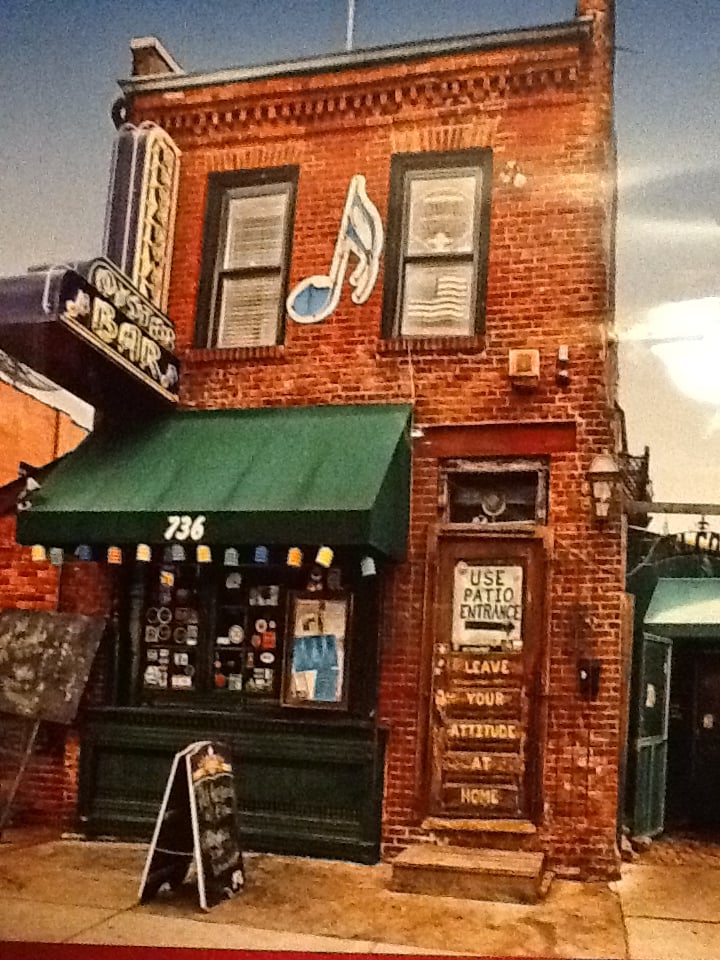

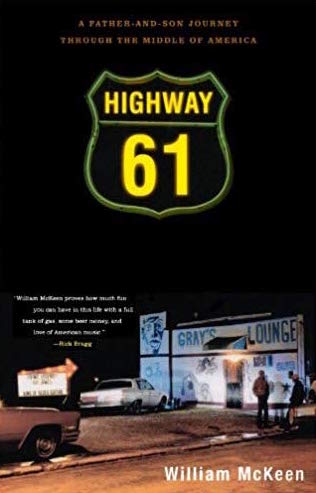

Note: Dick Dale died yesterday. I recall the night we met: my then-19-year-old son Graham and I were taking a trip down Highway 61, following the celebrated highway of the blues from the Canadian border to the French Quarter. The resulting book, Highway 61, came out in 2003 – words by me, photos by Graham. One of the memorable nights on the trip was at a wonderful hole-in-the-wall in St. Louis called the Broadway Oyster Bar, where we witnessed a performance by Dick Dale, King of the Surf Guitar. This is adapted from the book.

By dusk, the patio is filling, and Dick Dale’s bus pulls up on the street separating the Broadway’s patio stage from the White Castle next door. He stays on the bus until announced, and when he steps onto the sidewalk, my son is there with his camera. Dale points at him and says, “I don’t want to see that shit on eBay!”

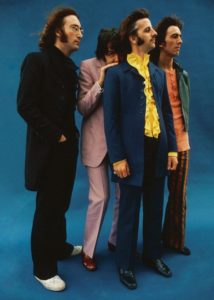

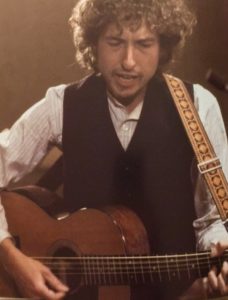

In the early days, Dick Dale was movie-star handsome in that anonymous television-actor sort of way, resembling Robert Horton, Ward Bond’s hunky sidekick on Wagon Train. Now in his sixties, Dale is striking in a different sort of way: a tall man, still with a sculpted face, with a high forehead and gray hair in a pony tail to the middle of his back. He wears a headband in keeping with the tribal themes in his recent albums, and he dresses entirely in black.

As soon as he hits the stage, he grabs his guitar and starts playing. The bottles of whiskey and vodka across the bar from me rattle with the thunder from his Showman amplifier. He has a drummer and a sleepy-eyed bass player as his perfunctory rhythm section, but the show is all his. In a lifetime spent listening to rock’n’roll music, I’ve never heard anything as loud as Dick Dale. Not only are the bottles rattling – my heart reverberates in my chest and my testicles resound with each gut-wrenching low run on the strings. It’s as much a sonic assault as a concert.

I’m content where I’ve been the last few hours, sitting at the corner of the outdoor bar, at the other end of the patio from the stage. The St. Louis night is still muggy and the city’s glow fades the stars overhead. Graham is over by the stage, stalking Dick Dale with his camera, worming his way through the crowd up front and, for part of the show, standing onstage, trying to get a shot of Dale’s mobile face as he plays. Dale looks his way and playfully jabs his guitar at his direction. Graham’s eyes glow. I’ve seen that look before, when he was little and I took him to Spring Training. The first Major Leaguer he saw up close was Orioles pitcher Rick Sutcliffe. Another time, we ran into hall-of-famer Bob Feller underneath the bleachers at an Indians game. He looked like any other retiree snowbird except for the fact that he was wearing a baseball uniform.

But as Graham grew up, baseball players gave way to musicians in his pantheon of greatness. As a guitar player, he worshipped Dick Dale, the man who nearly single-handedly invented reverb.

The Broadway is packed. I’m surprised that people in the nearby apartments and upscale remodeled homes haven’t called the cops to complain about the nuclear war at the oyster bar.

Dick Dale doesn’t mess around between songs – no long introductions, no background on his inspiration, no philosophical indoctrination.

“Hey you,” he nods toward a girl about 12 yards back from the stage. “You come up front, will ya? I like to see pretty girls up front while I play.”

He’d old enough to be her grandfather, but when she comes up to the stage, he kneels, offering her the neck of his Stratocaster. She runs her fingers suggestively down its long neck.

“I’ll stick around and sign autographs and talk after the show,” Dale announces into the microphone. “Anyone who wants their tits signed, line up over here at the side.”

His signature tune, “Misirlou,” is known to the youngest of the audience through its use in Pulp Fiction and Domino’s Pizza commercials. Old people like me remember when he was the baddest-ass in music, during the surf music days of the 1960s. He doesn’t play the standard version of “Misirlou” – he improvises, toying with the melody for 20 minutes. On one of his recent albums, he did the same thing with Duke Ellinton’s “Caravan.”

I stay at my perch at the bar, enjoying the night air and the crowd, not really watching the stage, where my son is playing cat and mouse with the guitar god. But then I notice a change in the texture of the sound – not Dick Dale’s sound but the sound of the audience. When I turn to look, Dale is walking off stage, toward the street. He’s got a wireless guitar. It still rumbles through his amplifier onstage, but he’s on the prowl and my star-struck son is right behind. Dale struts across the street to the White Castle parking lot.

It’s a surreal scene: There’s a car at the White Castle drive-thru window, and right behind it is a pony-tailed banshee wailing away on his guitar. Behind him is my son and a few other fans. When the car gets its order of bellybusters and drives off, Dale walks up to the window. He doesn’t say a word, but begins jamming his guitar neck at the bewildered minimum-wager at the cash register. What the hell is this, her face says.

Dale keeps walking. He’s out in the middle of Broadway now, dodging cars. Imagine the drivers’ fright when they see this tall monster, all in black, with his Rapunzel hair, walking down the centerline, all the while booming music from the amps back on stage. He turns and comes back through the front entrance of the bar, where all of the people who couldn’t fit into the patio-stage area are startled not only that they can finally see the guy – but that he’s elbowing them for space at the bar.

He comes back out on the patio and sits on the stool next to me. He hasn’t missed a note. He nods at the bartender that he wants a beer and she pours it down his throat while he continues to play. Graham has been stalking him the whole time, eyes big as pie plates, like Dick Dale is his pony-tailed pied piper.

True to his word, Dick Dale sticks around afterward, talking to anyone who wants an audience with the King of the Surf Guitar.

I tell him about our trip, about the free fall we’re doing from Canada to New Orleans and how lucky we were to be in St. Louis when he hit town. Talk about serendipity.

“You tell your friends to come out and see Dick Dale sometime,” he says.

A blonde woman with mascara sweat-pasted to her cheeks pulls down her shirt and presents her breast.

“Oh baby,” Dick Dale says. “You don’t know what this means to me.” He signs, “All the best, Dick Dale” in Sharpie across her flesh.

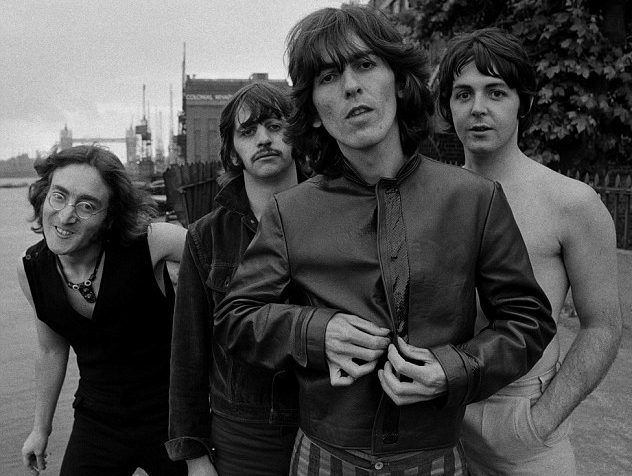

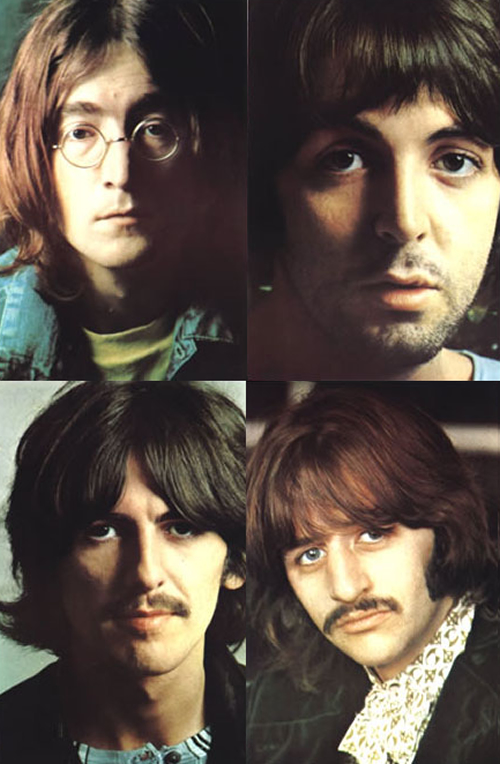

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard.

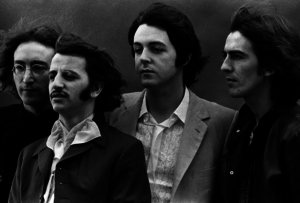

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard. Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

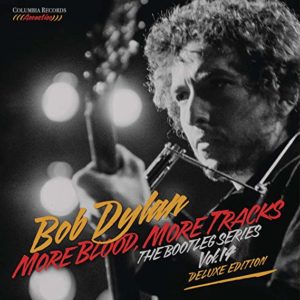

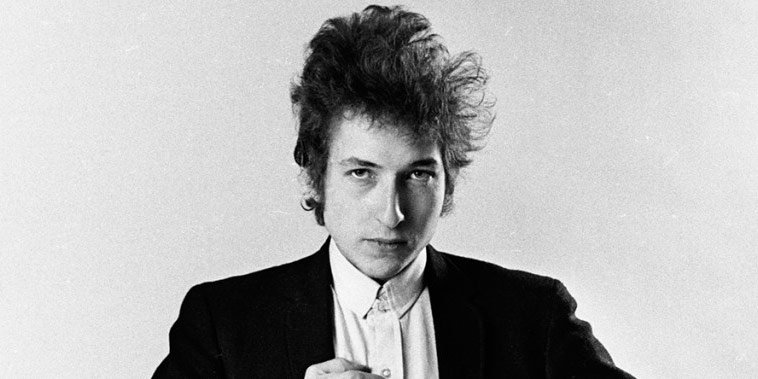

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

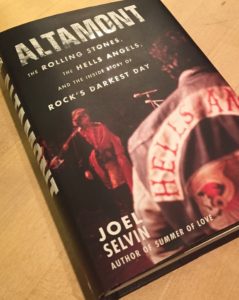

So this — a brief word of praise for Altamont by Joel Selvin.

So this — a brief word of praise for Altamont by Joel Selvin.