Screenwriter Robert Towne died this week. He was a master at his craft and was the genius behind Chinatown, Shampoo, The Yakuza, Tequila Sunrise, Greystoke and Personal Best. He also did uncredited script-doctor work on Bonnie and Clyde, McCabe and Mrs Miller, The Missouri Breaks and Heaven Can Wait.

Towne had a regular family of collaborators — Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty most prominently.

But he also worked with one of the great directors of the 1970s, that glorious decade for films. Those years gave us some of the greatest work from Martin Scorsese, Brian DePalma, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg.

And also Hal Ashby, often overlooked when it comes to the great directors of that era.

But let’s look at Ashby’s resume:

Shampoo, Harold & Maude, Coming Home, Being There, Bound for Glory, Eight Million Ways to Die and many others.

Not bad. That’s like my list of favorite films from the seventies (and a couple into the eighties). I think Being There is one of the great American films and the performance by Peter Sellers is a magnificent study in restraint.

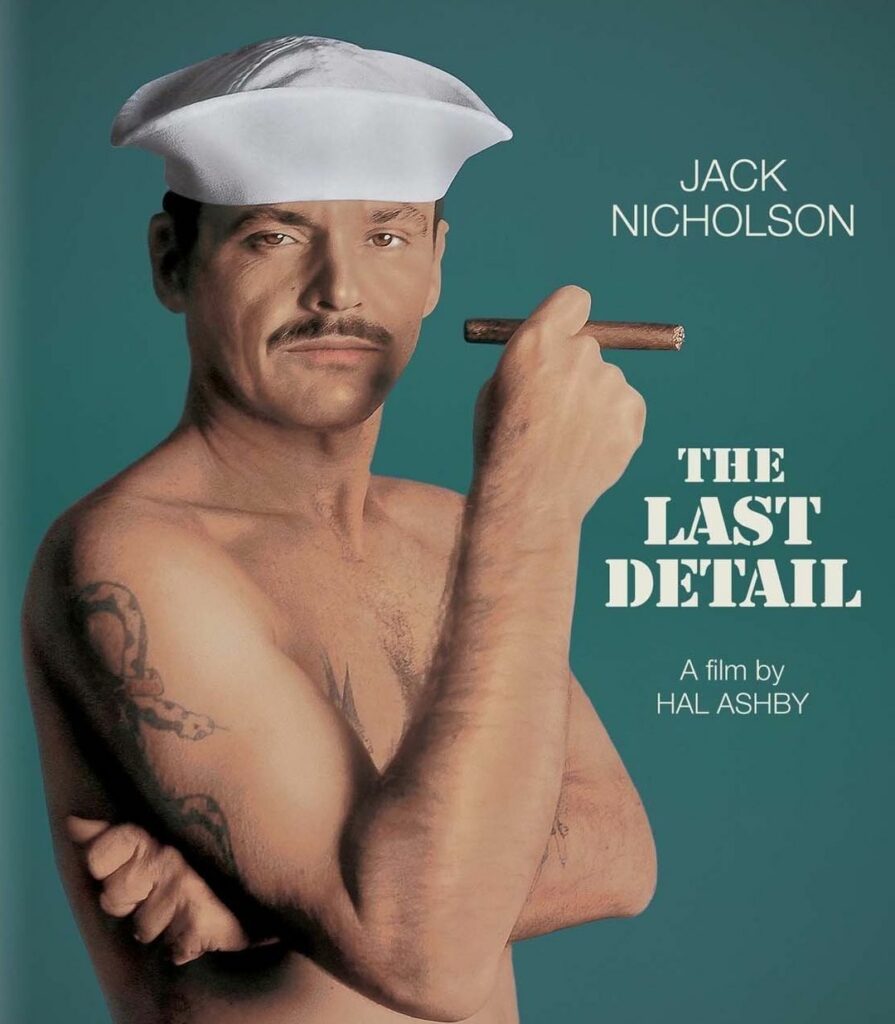

These two talents — Towne and Ashby- — intersected in 1973 with The Last Detail, based on Darryl Ponicsan‘s novel.

It’s not always easy to find this movie, so I was happy to see that Prime Video picked it up. It streams there.

This may be the most profane film ever made and Billy Badass Buddusky is one of Nicholson’s greatest roles.

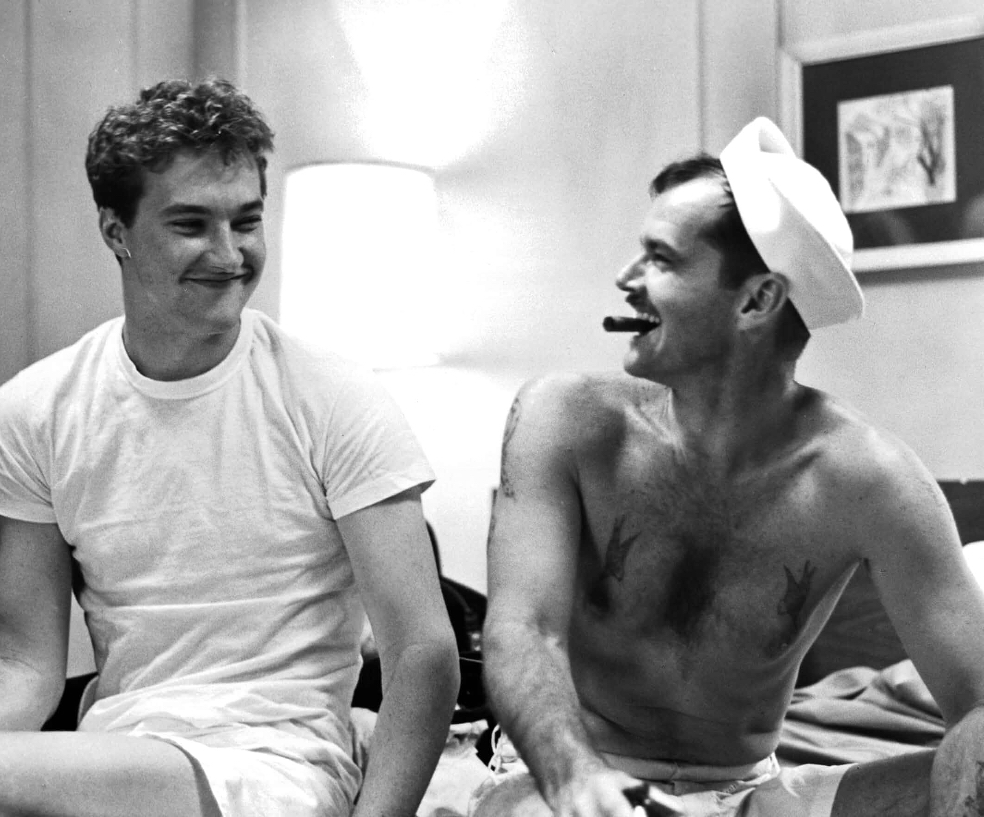

The plot is simple: sailors Billy Badass and Mule (Otis Young) are assigned to Shore Patrol duty in order to escort young Meadows (Randy Quaid) from Naval Station Norfolk to the Navy prison in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Meadows is a kid, a virgin, an innocent, a guy who hasn’t lived yet. He’s going to prison for eight years for trying to lift some money ($40, if memory serves) from a charity donation box.

The three of them have to pass through several states to get to Portsmouth and Badass and Mule decide to give the kid a dose of fun before he’s locked away.

As Billy Badass says, “No fucking Navy’s going to give some fucking kid eight years in the fucking brig without me taking him out for the time of his fucking life.”

Meadows isn’t even 21 so Badass and Mule take him to a bar when they hit New York City. The bartender refuses to serve them and when Billy Badass becomes belligerent, the barkeep threatens to call the Shore Patrol. Nicholson slams his piece on the bar and says, “I am the motherfucking Shore Patrol!”

Perhaps that scene is not as iconic as Nicholson’s diner scene from Five Easy Pieces, but it ought to be.

Nicholson and Young are excellent. Though Randy Quaid had made a couple of fims before this — notably, The Last Picture Show — this was the first sign of what an excellent actor he was. For those who only know him as Cousin Eddie from the Vacation films or for his sometimes-erratic behavior in his private life, his performance as Meadows will come as a revelation.

Badass and Mule don’t want to see Meadows to go off to eight years in prison without getting laid, so they arrange for the services of a prostitute, played by Carol Kane, in her screen debut.

I’m not a press agent for old movies, but I hope I’ve interested you in tracking down this excellent and oft-overlooked film.

Nicholson, Quaid and Towne were nominated for Academy Awards. Alas, there were no winners for The Last Detail. Ashby didn’t even get nominated.

Towne wrote the screenplay several years before the film was produced. Hollywood’s studio czars considered it too profane to film. When it was finally made, it set the record for use of the word fuck in a film.

I often say that the most important reason for the Internet to exist is to provide a platform for IMDB, the Internet Movie Database. Not only does it help us settle arguments about in what earlier film we’ve seen this or that actor, it also has fun stuff like trivia and quotes from films.

So below, from IMDB, some of Towne’s dialogue from The Last Detail.

Rest in peace, Robert Towne.

Buddusky ruminates on Meadows’ fate. The donation box from which he tried to lift the money was for the favorite charity of the wife of the Navy base’s commander.

Buddusky: Boy, they really stuck it to ya, didn’t they, kid! Stick it in and break it off. Up your giggy with a wah-wah brush, stick it in an’ break it off.

The three sailors come across a conciousness raising group and Meadows takes up chanting. This helps when they meet a beautiful woman at a bar.

Buddusky: If this guy gets pussy out of this, I’m gonna eat my fucking flat hat, man.

Mulhall: Yeah, and I’m going to start chanting too.

Meadows: [returns to table with Mulhall and Buddusky] Hey, you guys? Drop your socks and grab your cocks. We’re going to a party.

The New York bartender won’t serve Buddusky and company. He nods toward Young, who is black, and says he would only serve him because the law forces him to. Buddusky threatens to kick the bartender’s ass.

Bartender: You try it, and I’ll call the shore patrol.

Buddusky: I am the motherfucking shore patrol, motherfucker! I am the motherfucking shore patrol! Give this man a beer.

Meadows: I don’t want a beer.

Buddusky: You’re gonna have a fuckin’ beer!

Buddusky is frustrated by Meadows’ passivity.

Meadows: Hey, you guys mind if I say somethin’? That guy at the bar, why did you get so mad at him? I don’t blame him not givin’ me a beer.

Buddusky: Hey, don’t you never get mad at nobody?

Meadows: Well, sure I do, yeah.

Mulhall: Who do you get mad at?

Meadows: Not at somebody who’s doing their job.

Buddusky: Who, then?

Meadows: Injustice.

Buddusky: Bullshit! You never get mad at nobody. You’re just a pussy!

Meadows: I do too get mad.

Mulhall: Did you ever get mad at the old man for what he done to you?

Meadows: Well, he was just…

Buddusky: …doin’ his job. Hey, they’re gonna take eight years outta your life, man.

Meadows: Six years. You said six! [Buddusky told Meadows he could get two years off for good behavior.]

Buddusky: Hey, what the fuck difference does it make? You don’t even care about it.

Mulhall: Come on, Badass, that don’t help him.

Buddusky: Fuck help, fuck fair! Fuck injustice! Don’t you ever just wanna fuckin’ whomp and stomp on someone, bite off their ear, just to do it…? I mean just to do it, just to get it out of your system?

Badass and Mule ponder what prison will be like for Meadows.

Buddusky: He don’t stand a chance in Portsmouth, you know. You know that, don’t you? Goddamn grunts, kickin’ the shit outta him for eight years… he don’t stand a chance.

Mulhall: I don’t want to hear about it.

Buddusky: ‘Maggot’ this, ‘maggot’ that… Marines are really assholes, you know that? It takes a certain kind of a sadistic temperament to be a Marine.

Badass takes Meadows to an adult bookstore, to prepare him for his deflowering

Meadows: [looking at porn] Are they really doing that when they take that picture?

Buddusky: [pause] Well, kid, there’s more things in this life than you can possibly imagine. I knew a whore once in Wilmington. She had a glass eye… used to take it out and wink people off for a dollar.

Meadows prematurely ejaculates while undressing with the prostitute. She considers her transaction with Meadows to be over, meaning he will remain a virgin. This is intolerable to his mentor.

Buddusky: You wanna try it again, kid?

Meadows: Yeah.

Buddusky: [to prostitute] Okay, honey.

Mulhall: Don’t worry about it, kid… plenty more where that came from.

Buddusky: You got all night, kid.

Earlier, before going to the brothel, the sailors hook up with a woman in a bar. She and her friends offer to take the sailors to a party, but they have no interest in anything other than chanting and lamenting the military industrial complex.

Meadows: If you’re Catholic, do you think it’s, uh, sacrilegious to chant?

Buddusky: Did it get you laid?

Meadows: No.

Buddusky: Then, Meadows, what the fuck do you want to go on chanting for?

Mulhall: Chant your ass off, kid. But any pussy you get in this world, you gonna have to pay for, one way or another.

Buddusky: Hallelujah!

Mule lays out parameters for his relationship with Badass.

Mulhall: I consider myself in jeopardy with you, man, understand? In jeopardy. This ain’t no farewell party an’ he ain’t retirin’. Understand? He’s a prisoner an’ we’re takin’ ‘im to the jailhouse. An’ you have a tendency to forget that. You’re a menace, man. You ain’t no simple shit, Bad-Ass, you’re a motherfuckin’ menace. But from now on, MAA can go piss up a rope! You ain’t no honcho! An’ I wanna hear no more of this horseshit psychology jive! No more turnin’ that boy’s head around to prove what a fuckin’ big man you are! You’re a lifer like me! Navy’s the best thing ever happened to me, an’ I don’t want’cha to fuck me up, ya understand?

Buddusky’s response to a woman’s sarcastic remark about his navy uniform.

Buddusky: You know what I like most about this uniform? The way it makes your dick look.