The Campfire Rule

This is the introduction to Critical Interpretations on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (upcoming)

So far as we know, this is it. We can speculate about the Great Unknown, but none of us knows for certain what awaits when the noble pump stops beating and the brain goes out of business. About that, we can only guess.

In the end, what matters is what we leave behind. If we follow the campfire rule, we leave this campsite — our world — better than when we found it.

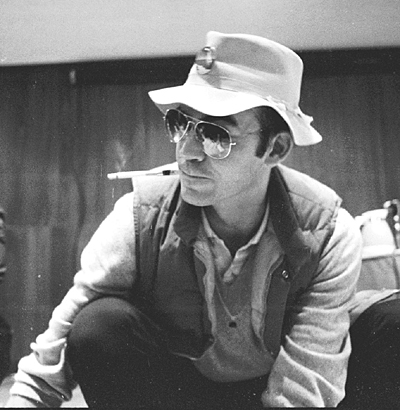

Hunter S. Thompson left us his work, a remarkable collection of writing in which he cast his wary and astute eyes upon the planet’s cavalcade of strangeness during his term as protoplasm walking the earth.

Thompson’s gifts were immense and his writing endures deep into the decades after his suicide. His astonishing wordplay and operatic anger, unleashed when the world disappointed him, were often mistaken as calls for anarchy or rebellion. Read his work more closely, and see that his flights of invective echoed the hurt and anguish of a loyal yet spurned lover.

He cherished the idea of his country and its aspirational documents. The nation laid down a powerful blueprint in the Constitution, yet was no closer to achieving its goals two centuries deep into its history when Thompson began taking the nation at its word. He saw it as his solemn duty to hold America to account.

Thompson did so through his distinctive writing, in a style so intoxicating that many sought fruitlessly to mimic it and others just gave up on the whole imposture of social commentary. With a resonant voice like Thompson’s in the arena, the standard was set so high that trying to compete with that powerful style was futile.

It was called gonzo and though often imitated, it was never duplicated. It was as if Thompson was the sole proprietor of a literary magic shop. So many definitions were attempted for gonzo, but eventually, the best one was this: whatever Hunter Thompson wrote. He was a virtuoso with language and his writing was best performed aloud, so musical was his prose.

The fact that so many line up to declaim that this [insert title here] is his greatest work speaks to the enduring relevance and brilliance of his writing. Consensus does not exist.

Though an unknown who supported his young family by selling blood and plasma, Thompson committed some of his finest writing in his early years. When it was published in the final decade of his life, The Proud Highway, his first volume of collected correspondence, showed him bursting into the world, nearly fully formed as an artist and entirely self-educated. His writing for the National Observer, the Sunday edition of the Wall Street Journal, was as lively as a rattlesnake in the bathtub and nearly as unexpected. Then there was his revolutionary foray into participatory journalism, Hell’s Angels, and the struggles in subsequent years to wrestle between covers some hokey-sounding bullshit about “the death of the American Dream.” Eventually that wheel-spinning informed Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a book nearly as perfect as The Great Gatsby. From there, his work grew even more urgent with his campaign reporting for Rolling Stone.

His political writing cursed him with volcanic celebrity that crippled him as a reporter, so he transitioned into the late-century equivalent of H.L. Mencken, becoming the sage of Woody Creek, dependent on the reporting of others, via satellite television. There were some weaker moments along the way, and the fame monster dogged him, but after a few autobiographical collages and the second magnificent volume of letters, Fear and Loathing in America, we were left with a rich and singular body of work.

Pick a best out of all that? Who, this side of Sophie, could make such a choice?

Time, that relentless old fool, will render judgment long after we are gone. For our purposes today, we here consider Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. It may be the most sustained piece of work he published. He said his writing was a series of peaks and valleys and for there to be highs, lows were necessary. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is notable for its absence of lows.

Collected here are some considerations of that seminal work through a dozen-plus prisms, offered by some of the best minds ever to interpret Thompson. This is, as his friend Tom Wolfe might’ve called it, a virtual weenie roast of American literature.

We find ourselves two decades into the post-Hunter Thompson world, and we seek landmarks to allow us to access the man and his work. He chose to take himself out back in 2005, and would no doubt be amused by these proceedings. But he would also take pride that his work endured and was, in fact, still being discovered by those not yet born when he pulled the trigger that night at Owl Farm.

Hunter Thompson’s writing was a product of its time and also a signpost for America in its disarray. His commentaries, though knee deep in the moments he chronicled, have remarkable coherence and meaning today. His rants and rages have staying power.

He followed that campfire rule. We are better because he was here. In his work we find unfurled the folly and majesty of human existence. He left us a template for skepticism, and deep love for the American dream. He offered a complex and liberating point of view that bequeathed to readers a way of seeing, a roadmap to helping us find the right kind of eyes. His standards were ferociously high.

He would want us to know that the American Dream was still a possibility and despite the agonies and heartbreak of modern political experience, we can still bring our aspirations into reality. We cannot give up.

He never gave up, until he did.