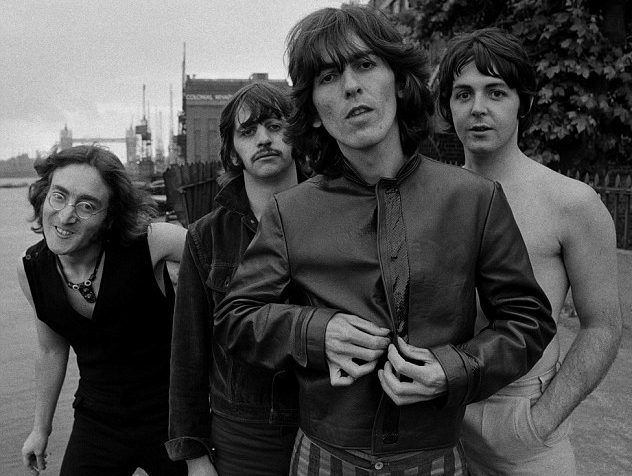

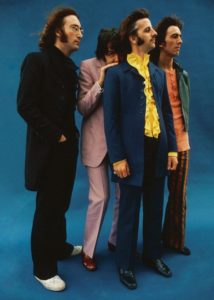

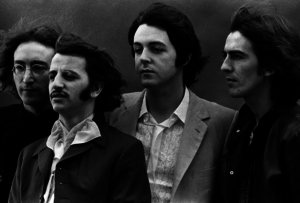

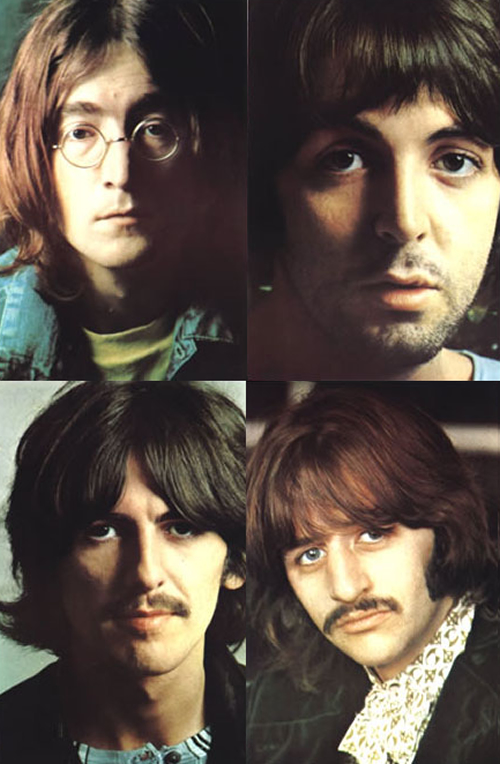

For a week now, I’ve been immersed in the 50th anniversary edition of the White Album, the record officially known as The Beatles, released November 22, 1968.

It was the first Beatle album that I bought new. My sister was at the right age when the Beatles hit in 1964. I watched them on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’ that February and sat front and center for A Hard Day’s Night at the theater that summer.

I liked the music, but music itself hadn’t really hit me. Not rock’n’roll at least. I was still into Henry Mancini and Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals — but that’s another story.

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard.

Things had changed by 1968 and I was ready when the White Album hit. Back then, young sprogs, our parents didn’t just buy us stuff and we didn’t get handed an allowance. The folks expected us to work for money. And since the White Album was a double-album, I’d need to work extra hard.

That fall, my parents had moved to a new house on a heavily wooded lot outside Bloomington, Indiana. They’d paid to have a few trees removed around the back deck, but the massive stumps were left behind. Stump removal was my job. My father’s going rate was five dollars per.

Owing to blisters and exhaustion, I couldn’t do too many stumps at a time. Gradually, using axes and shovels, I cleared all but a few. In order to buy the White Album, I needed to find a big bastard out in the yard.

I found something suitable and asked my father if I could have $10 for it, since it was such a large and sprawling fucker. The old man agreed. I think he knew I had the hunger to buy something that was otherwise out of reach.

I attacked that thing with the ferocity of Alan Ladd in Shane. He and Van Heflin took on a monster stump and together pulled its stubborn carcass from the ground.

Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

Without help, I spent a day working in the back yard. When I called my father outside at dusk, he marveled at my work, then handed me a $10 bill. I rode my bike to the Woolworth’s — luckily, owing to the early sunset of November — only a half mile away. The album was mine.

I’m not sure I can make a Sophie’s Choice with Beatle albums. I’ve always been partial to Rubber Soul. Revolver still sounds great all these years later. Then there’s Abbey Road. On the day it was released — a year after the White Album — I remember tear-assing down to Discount Records on lunch break to pick it up. I held it , still sealed, in my fingers on my desktop, the envy of my social set, since I had it first.

But the White Album was something unique. It both pleased and mystified me. Every note and every sound became part of my sinews. Over the years I haven’t needed a device to play the record. It’s always there, ready to unspool in my skull.

The 50th anniversary edition — six CDs, one BluRay — is a worthy presentation for such a vital album. The Beatles always so well captured the essence of their times, and they matched the brutality and change of 1968 with an album that was chaotic and magnificent.

I not only rediscovered this great old album. I found things I didn’t know I was looking for.

The box arrived in the mail and almost immediately I hit the road for a drive to New York for the weekend. For my road music, I grabbed only the last four discs — the demos cut in the spring at George Harrison’s house, and three discs of studio outtakes, including songs that never made it on to the album, including ‘Hey Jude,’ ‘Sour Milk Sea,’ ‘Child of Nature,’ ‘Across the Universe’ and others.

I was alone, so I played the discs one after another at thundering volume. I’d had most of the stuff on bootlegs, but the quality of this set is superior. I’ve always enjoyed these archival sets. Bob Dylan has 14 volumes in his Bootleg Series, and it’s great to hear his early takes — to hear, say, what ‘Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues’ sounded like about six minutes before genius showed up. There’s a Jimi Hendrix archival set that makes his music sound ordinary, right before his brilliance caught fire.

The Beatles have not done the ‘official bootleg’ thing quite as much, but the White Album is a great place to show the anatomy of the creative process.

Here are some highlights (for me):

- Hearing John work through ‘Julia,’ the song about his mother. To hear him on the talkback with engineer Chris Thomas … to hear his voice again … chokes me up. The same happens when you hear George order a sandwich before recording ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps.’ It’s sad those voices are no longer in the world.

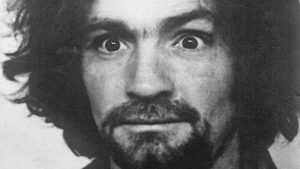

- I never much liked ‘Helter Skelter’ because of its lumbering sound, and began to actively hate it after Charles Manson co-opted it. Oddly, on this set it’s one of my highlights. After blasting through it, Paul says, “Mark it ‘Fab,’” and it is.

- I always wondered about that ditty (‘Can you take me back where I came from’) that Paul sings as the sound montage of ‘Revolution 9’ begins. Here you hear him work through it, trying to develop it into a full song. Turns out it was perfect as a fragment.

- Hearing all four Beatles sing ‘Good Night.’ On the original release, Ringo sings it with an orchestra. I could never decide if — since it followed the madness of ‘Revolution 9’ — the song was intended to end the album on a reassuring or ironic note. On one of the takes, Ringo sings and the other three lean into a microphone to harmonize. It’s not the greatest performance, but to hear those four voices together again is deeply moving.

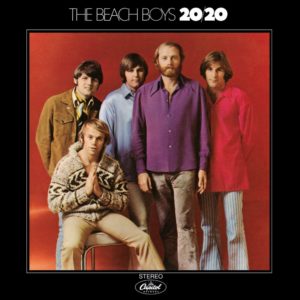

- Hearing three Beatles (Ringo, depressed, took a break during the sessions) playing ‘Back in the USSR’ in a lower key. They sped up the tape to give the song its sonic magic.

- Hearing John finger-pick his way through ‘Dear Prudence’ and Paul do solo run-throughs of ‘I Will’ and ‘Mother Nature’s Son.’

All the way down to the city and all the way back, I blasted those four discs.

Listening to the White Album itself was sort of an afterthought for me. My ears are not sophisticated and when people talk about new remixes, I sort of glaze over.

So it was more out of a sense of duty that late the night of my return, I went downstairs to my basement office and music room to put on the remixed White Album, just so I can say I listened to it.

Wow.

Do you remember the old Maxell tape advertisement, from back in the Seventies — the windblown and mindblown guy in the easy chair? That was me as ‘Back in the USSR’ boomed from my speakers. I listened to the whole thing straight through. It was brilliant.

‘Tis the season, apparently, for expensive box sets.

Just the week before, I’d been spelunking through Bob Dylan’s back pages. As the first victim of bootleggers, he began bootlegging himself back in 1991 when he launched his Bootleg Series. He’s up to Volume 14, More Blood, More Tracks, six discs collecting the 1974 recordings leading to his classic Blood on the Tracks.

As with the White Album outtakes, I’d had bootlegs devoted to the Blood on the Tracks sessions. He recorded much of the album on the day I turned 20 — September 16, 1974 — and ran through monstrous numbers of takes.

After a few furious days of recording in New York, an album was assembled. Columbia Records designed a cover, commissioned liner notes from Pete Hamill, and readied the album for release.

Then a funny thing happened on the way to the hit parade.

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

Dylan had second thoughts. He played the acetate of the album for his brother while visiting Minnesota in December. David Zimmerman told big brother he could do better. Or something. But he hired a studio, found some local musicians, and got Big Brother Bob to re-record half of the album.

Columbia Records had a collective coronary and the album was delayed a month. To save time and money, the record company went with the original album cover, meaning the Minneapolis musicians did not get credited, though they had recorded half the album.

Eventually, the original recordings — some of them, at least — leaked out.

Conventional wisdom — meaning bullshit spewed by clueless fans such as myself — held that Dylan withdrew the original recordings because they so well chronicled the pain and suffering of a man mired in heartbreak and despair. The album supposedly told the story of his abandoned love as his marriage crumbled. Dylan, his voice strained, was a testament to vulnerability. (Dylan denied this, of course, saying the album was inspired by the short stories of Anton Chekhov.)

Now, however, Dylan has shared all of the takes — they are legion; six discs worth — from the New York sessions. Alas, no outtakes from the Minneapolis sessions exist, but we do get all of the master takes, minus the echo added in post production.

Both the White Album and More Blood, More Tracks show deep-dive insight to the creative process. Both the Fabs and Dylan show us how songs grow and evolve. But these huge collections are more than mere curiosities for music geeks. These are further explorations and discoveries of this music we’ve carried within us for a half century.

Listen again to the acts we’ve known for all these years. You’ll be surprised by all of the things you haven’t heard.

There are a few neighbors with whom I converse, but mostly I have smile-and-nod relationships with the people in the houses around me.

There are a few neighbors with whom I converse, but mostly I have smile-and-nod relationships with the people in the houses around me. This girl is in second or third grade, I would estimate, and her younger sister I would guess is in kindergarten. Their parents are nice in a nod-and-smile way, and her father is the only person in the neighborhood, other than me, to do yard work. I am his Brother of the Bramble. Everyone else hires landscape companies.

This girl is in second or third grade, I would estimate, and her younger sister I would guess is in kindergarten. Their parents are nice in a nod-and-smile way, and her father is the only person in the neighborhood, other than me, to do yard work. I am his Brother of the Bramble. Everyone else hires landscape companies.

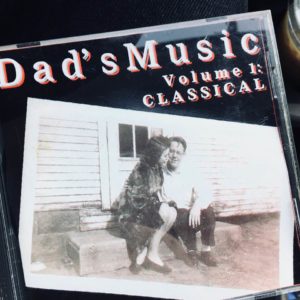

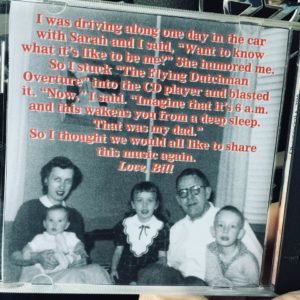

I sent these sets to my mother, brother and sister with instructions that they not be opened until June 14, dad’s birthday.

I sent these sets to my mother, brother and sister with instructions that they not be opened until June 14, dad’s birthday. Think of how much of your life is defined and preserved in musical memory. I was driving to the ferry terminal this morning, serenading — at top volume — the sleeping denizens of Nantasket Avenue with Wagner’s ‘Death of Siegfried.’

Think of how much of your life is defined and preserved in musical memory. I was driving to the ferry terminal this morning, serenading — at top volume — the sleeping denizens of Nantasket Avenue with Wagner’s ‘Death of Siegfried.’

Danny and Mark had set up tables on their back deck, out in the open, and had enough chairs to seat 20 or so.

Danny and Mark had set up tables on their back deck, out in the open, and had enough chairs to seat 20 or so. I became aware of the quiet. Everything stopped, but of course it didn’t.

I became aware of the quiet. Everything stopped, but of course it didn’t.

I gradually came back but didn’t move, so comfortable was I in my terrycloth cocoon. Like a good boyfriend, Ryland carried Sarah upstairs and held her hair back while she bent over the toilet, vomiting. Savannah appeared at her side, in her red party dress.

I gradually came back but didn’t move, so comfortable was I in my terrycloth cocoon. Like a good boyfriend, Ryland carried Sarah upstairs and held her hair back while she bent over the toilet, vomiting. Savannah appeared at her side, in her red party dress.

But I found it in my ‘recent calls’ folder. A missed call from the 305 area code, meaning South Florida or the Keys. The first 305 I could think of was Nicole’s mother. But she was in my contacts, so her name would have come up. Plus, she’d been dead since March. I’d be surprised if she called.

But I found it in my ‘recent calls’ folder. A missed call from the 305 area code, meaning South Florida or the Keys. The first 305 I could think of was Nicole’s mother. But she was in my contacts, so her name would have come up. Plus, she’d been dead since March. I’d be surprised if she called. They had called my train and I walked stiffly toward Track 13. Of course, Track 13. What rotten luck.

They had called my train and I walked stiffly toward Track 13. Of course, Track 13. What rotten luck.

(And a few of the apparently used the book as a coaster, a practice I find reprehensible.) Still, this book has been read by many hands — hands of people I loved.

(And a few of the apparently used the book as a coaster, a practice I find reprehensible.) Still, this book has been read by many hands — hands of people I loved. But I was into death. From the time I was in single digits, I had a sense of impending death.

But I was into death. From the time I was in single digits, I had a sense of impending death. The astronauts were played by Jack Klugman, Ross Martin and Frederick Beir. As they debated what to do it occurred to me that I was going to die someday.

The astronauts were played by Jack Klugman, Ross Martin and Frederick Beir. As they debated what to do it occurred to me that I was going to die someday.

For someone who drove so much — long, madman drives between Florida and Indiana when I’d steal long weekends to go visit my older kids when they were little — I had a library of death scenarios from the highways. I certainly saw enough accidents and had a lot of close calls. One time, a guy intent on suicide jumped in front of my car but my cat-like reflexes (if you knew me, you’d realize that’s funny) allowed me to swerve at the last minute. There’s a herd of deer in the world that would not exist had I not be able to respond so quickly.

For someone who drove so much — long, madman drives between Florida and Indiana when I’d steal long weekends to go visit my older kids when they were little — I had a library of death scenarios from the highways. I certainly saw enough accidents and had a lot of close calls. One time, a guy intent on suicide jumped in front of my car but my cat-like reflexes (if you knew me, you’d realize that’s funny) allowed me to swerve at the last minute. There’s a herd of deer in the world that would not exist had I not be able to respond so quickly.