Pulling the Thread

My agent suggested I do a book on Bob Woodward. I was dubious, but ended up having a lot of fun with the research and writing. Alas, my agent found that though people liked Woodward’s books, they didn’t think a book about him was necessary.

. . . . . . . .

Copyright © 2025 William McKeen

“If there is no accountability, another president will feel free to do as he chooses. But the next time there may be no watchman in the night.” [Rep. James Mann, D-South Carolina, during the House Judiciary Committee vote, July 29, 1974]

He was about to become the most famous security guard in America. It was just after midnight on June 17, 1972, and Frank Wills was making his rounds at the Watergate Office Building in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington.

The Watergate complex covered 10 acres and housed six buildings, a mixed development of businesses, agencies and desirable apartments in one of the most popular neighborhoods for civil-service employees and young members of Congress. Certain key members of the administration of President Richard Nixon also lived there. John Mitchell, the former attorney general, shared a large Watergate apartment with his flamboyant Southern-Belle wife, Martha. The president’s personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, lived there as well.

Down in the security office that night, Wills had just clocked in for his midnight-to-dawn shift and began his rounds, working his way up through the primary office complex at 2600 Virginia Avenue Northwest, starting in the subterranean garage. He was 24, and had moved a lot in his young life. Born in South Carolina, he’d relocated to the Midwest with his mother after his parents’ divorce. He dropped out in the 11th grade, but eventually completed his high school degree through the Job Corps.

He soon got a coveted and secure job at the Ford plant in Detroit but suffered from asthma, and the assembly line work aggravated his condition. He gravitated south and in Washington, found a few hotel jobs before landing the guard position at the Watergate.

He got the graveyard shift, and wasn’t happy about it. “I’d been in the job about a year and wasn’t going anywhere,” he said. “A white fellow came in after I did and they made him a lieutenant. I was a corporal, making just $80 a week.”

That night in 1972, Wills left the security office at 12:05 to start his rounds. He returned at 12:20 and noted a few things in his logbook that were odd, but not concerning.

On the second basement level, he’d found a stairway door from the parking floor unlocked, with masking tape over the locking mechanism. Someone wanted to keep the door to the stairwell open. It was obvious; the tape was affixed horizontally, extending out onto the surface of the door. Someone behaving surreptitiously would probably run the tape vertically over the lock, so it couldn’t easily be detected.

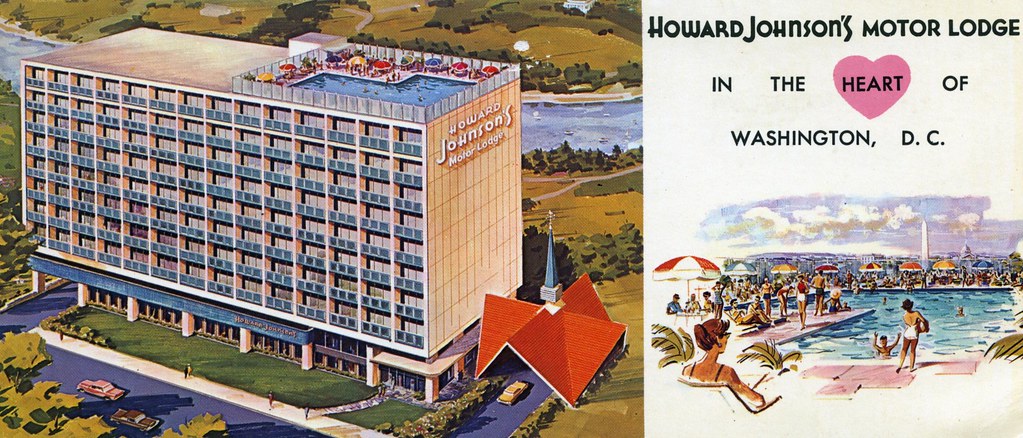

Wills removed the tape, and tossed it in the garbage. When he returned to the office, he noted the door tape in the logbook, then crossed the street to the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge. The restaurant there stayed open all night, so Wills got some take-out. He took it back to the office and ate.

At 1:47 am, he set off on rounds again. When he got to the door on the second basement level, he again found masking tape, horizontal, over the door lock. “I just got to thinking there’s somebody in this building besides me,” Wills said. Who worked in the middle of the night in an office building, except for custodial and security staff?

Wills called the Second District of the metropolitan police. He had not been issued a gun. “With just a can of Mace, I couldn’t confront a burglar,” he said.

His discovery set into motion a political scandal that resulted in the resignation of the president of the United States.

. . . . . . . . . .

The police dispatcher took Wills’ call and radioed Officer Dennis Stephenson. He had just pulled into his parking space outside the station and asked the dispatcher to try to find someone closer to the Watergate. He had paperwork to do from his shift and didn’t want to delay clocking out with a routine call from a security guard. Plus, he told the dispatcher, he was low on gas. The dispatcher gave him a pass.

Stephenson was in uniform. His three colleagues who answered that call were not.

They were a plainclothes crew who had finished their shift, but stopped to share a drink at an after-hours nightclub. They got the call and since they were near the Watergate, they decided to go talk to the security guard. It sounded routine and would be worth the overtime.

Across the street, on the seventh floor of the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge where Frank Wills had gone for his take-out, a lookout stood on the seventh-floor balcony of his room, watching the Watergate with binoculars. He had the perfect vantage to see what was going on in the illuminated sixth-floor Watergate office of the Democratic National Committee.

The lookout was Alfred Baldwin. With his partner, Jim McCord, he had set up this operation. Baldwin watched for signs of trouble while McCord and his associates — mostly Cuban exiles, Commie-haters to the man — broke into Democratic headquarters to plant surveillances devices. He communicated with them by walkie-talkie. It was routine stuff.

Nearly two in the morning. Baldwin was bored, so he turned on the television and watched middle-of-the-night movies with one eye, keeping his other eye on the burglars across the street.

A car pulled up outside the Watergate and three men got out. If they’d been wearing uniforms, that would’ve gotten Baldwin’s attention. “I wondered if that meant anything,” Baldwin said, “but I didn’t use the walkie talkie at that time.” As it was, he shot the three men a brief glance, saw the burglars in the lighted suite of offices, then got back to the television.

The burglary crew had been there before. Over the Memorial Day weekend, McCord and his fellow burglars had broken into Democratic National Headquarters and planted listening devices on phones, including the private line of party chairman Larry O’Brien. Baldwin monitored the recorded calls for nearly three weeks and soon realized one of the bugging devices was malfunctioning. So a return trip was set for June 17.

The occupants of the Democratic headquarters had been unaware that they were under surveillance.

Baldwin had transcribed the calls and they were typed, edited and shared by the offices of the Committee to Re-Elect the President, then presiding over a planned coronation of Richard Nixon for a second term.

The Nixon campaign had been concerned about the early Democratic front runner, Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, but he had self-destructed at a campaign event during primary season, babbling about how newspapers had mocked his wife.

Another foe was Nixon’s opponent from 1968: Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota. But Nixon had defeated him then and so casting off the “loser” tag would be difficult for the former vice president. He also had a tendency to babble.

The Democrats were on track to nominate Senator George McGovern from South Dakota. The Republicans couldn’t have scripted it better. McGovern came from a sparsely populated state nearly bereft of electoral votes and he had picked up the pacifist mantel carried by Robert Kennedy in the 1968 campaign. A pacifist — so said the Republican Party line — was very nearly a Communist. So the burglars saw it as their mission to ensure McGovern’s defeat.

McGovern was doomed. Nixon could cash his check now; there was no doubt he would be re-elected, running against that guy.

Nonetheless, there they were: the burglars on the sixth floor of the Watergate, across the way, trying to gather intel that would harm the Democratic Party and its nominee. Baldwin glanced at the burglars now and then through the binoculars.

He knew the rewards from the break-in were few; the risks were legion.

The three plainclothes officers — John Barrett, Paul Leeper and Carl Shoffler — met Wills at the security office. He took the discarded tape from the garbage can and demonstrated the sloppy taping job the burglars had used. Wills said he would accompany the officers upstairs, but a buzzer alerted him that he was needed elsewhere, to let a tenant out of the building. One of the police officers asked Wills to stay in the main lobby when he was finished with the tenant. Watch for anyone trying to escape, they told Wills.

Up on the eighth floor in the stairwell, the officers found another taped door lock. They made a quick check of the floor and found nothing suspicious and decided to split up: Barrett went to the ninth floor and planned to work his way down. Leeper and Shoffler decided to start their check the seventh floor and go down to ground level.

They had just started down when they found another taped door lock on the sixth floor. Barrett was summoned and joined his colleagues on a search of that floor.

The Democratic National Headquarters was on the sixth floor. The office suite had two dozen private offices, four secretarial pools, several other smaller offices for secretaries and assistants, a mail room and a switchboard room. The brightly lit windows facing Baldwin at the Howard Johnson’s were from the private office of Spencer Oliver, who coordinated with state democratic committees, the treasurer and the communication staff. There was a balcony outside Oliver’s room. The office of O’Brien, the party chairman, was across the suite, with a window facing southeast, toward the other buildings in the Watergate complex.

Two of the police officers, Leeper and Shoffler, went out on the balcony and saw that the lights were on in one of the offices. Both of them were casually — even sloppily — dressed. Shoffler carried a flashlight and drew his gun. He looked across the way and saw Baldwin standing on the balcony of the Howard Johnson’s, peering at them. “Do you think he’ll call police?” he asked Leeper.

Baldwin stepped inside his room, suddenly alarmed. He saw the men on the Watergate balcony go back inside the building and begin turning on lights.

He picked up the walkie talkie. “Base to any unit.”

A voice crackled back. “What have you got?” Despite the poor sound quality, Baldwin recognized the voice of Howard Hunt, one of the leaders of the surveillance mission. Hunt was in the hotel section of the Watergate complex.

Baldwin was pretty sure that all of the people in his crew were dressed in suits. He asked Hunt to confirm, which he did.

“Well, we’ve got a problem,” Baldwin said. “We’ve got some people dressed casually and they’ve got guns. They’re looking around the balcony and everywhere.”

Hunt began barking into his walkie talkie, trying to raise the burglars. Baldwin figured they might have picked up the chatter, because the lights were turned off. He also feared they turned off their walkie talkies.

John Barrett, with gun drawn, worked his way into the committee’s office suites. He approached a corner office and stood motionless, becoming accustomed to the pitch black. Eventually, he recognized the shadow of a man’s arm in the darkness.

“Hold it and come out,” he shouted.

The man slowly stood. So did others, hiding behind file cabinets. They raised their arms. “Be careful,” one of them said. “You got us.”

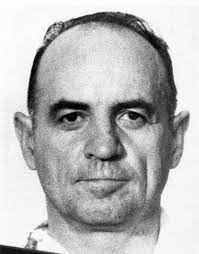

Jim McCord approached the undercover detectives on a collegial level, sort of a cop-to-cop greeting. “What are you people?” he asked. “Are you metropolitan police or what?”

But there was no small talk. Now the three officers lined up the intruders: Burglars in business suits, wearing surgical gloves.

Odd.

Baldwin watched helplessly from across the street. He watched as police cruisers pulled up to the building. They were marked this time, with throbbing bubble tops flashing. “There was all kinds of police activity,” Baldwin recalled. “Motorcycles and paddy wagons driving up and guys jumping out of patrol calls and running up to the Watergate.”

As Baldwin watched the drama unfold from the balcony, he saw two men sauntering out of the hotel property on the Watergate grounds. One of them looked up, directly at Baldwin. It was Howard Hunt. Hunt and his companion got into a car parked in front of the Watergate apartments and drove away.

Within hours, the news was out.

. . . . . . . . .

For decades, the Washington Post was the number-three newspaper in a three-newspaper town. By the time of the Watergate break-in, it was asserting itself, thanks to an aggressive editor and a supportive publisher. But for years it had been an also-ran, behind the Washington Evening Star, the establishment newspaper, and the Washington Times-Herald, a sensationalist paper that followed the blueprint drafted in the previous century by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

Founded in 1877, the Post had seen glory days, and there had even been a piece of music composed in its honor, known to every kid who ever played in high school band, “The Washington Post March.”

Washington was the nation’s capital, but it was also a parochial Southern city. The big dog in town, the Star, helped maintain the status quo, including the city’s ingrained segregation. The irony of segregation in that particular city was not lost. Yet the Star remained the bible of the establishment.

At its worst financial moment, in 1933, the Post came under the stewardship of Eugene Meyer. He was a financier and former chairman of the Federal Reserve, who had established the company that became Allied Chemical. In short, when he bought the Post at a bankruptcy sale, he knew nothing about journalism.

For a couple of decades, he drained his fortune to support the paper, which finally began to turn a profit in the early fifties. By then he had found the newspaper’s savior: his son in law.

Philip Graham was raised on a houseboat in the Everglades, but eventually his family made enough money to send him off to college. His father was an early dairy farmer in the wilds of South Florida, and as the city of Miami began to boom in the twenties, the family fortunes improved. They moved off the houseboat and young Phil enrolled at the University of Florida.

At the campus upstate, Phil was greeted as a gawky hillbilly — at six-foot-two and 110 pounds, classmates nicknamed him Stringbean. But he was a superb and popular student, president of the university’s honor society. The next step was Harvard Law School. There his classmates again mocked his appearance, but then fell into awe at his intelligence and academic cool.

At school he met another hillbilly savant, Ed Prichard of Kentucky. They soon emerged as the superstars of their class and the favored surrogate sons for beloved professor Felix Frankfurter. When Frankfurter was nominated to the United States Supreme Court, it was assumed that he would have to choose between these golden boys when he selected his law clerk.

Frankfurter came up with a genius plan: he hired Prichard as his clerk, then arranged for his new colleague, Justice Stanley Reed, to have Phil Graham on his staff. After that year was done, Graham would clerk for Frankfurter. As David Halberstam wrote in The Powers That Be, his history of big-media institutions, “In football, it is known as red-shirting, in the arms race as stockpiling.”

Graham arrived in Washington in 1939, an intoxicating time. The best and the brightest minds were there, fulfilling the mission of Roosevelt’s New Deal government and preparing for war. Graham was planning to return to Florida, enter politics at the grass-roots level, and work his way up through Sunshine-State government – and perhaps further, perhaps to the presidency.

But two things happened.

Number one: Washington. It truly intoxicated.

Number two: he met Katherine Meyer.

Eugene Meyer’s daughter was in her early twenties and dating Johnny Oakes. Though he didn’t spell his last name Ochs, he was part of that clan: the Ochs-Sulzberger family that owned the New York Times. He was in Washington, working for the Post, and had fallen in love with Katherine — known as Kay to her friends. Theirs seemed like a logical pairing, and engagement was assumed. It would be like a journalistic royal wedding — a joining of the Times and Post families. It made sense.

But then Kay Meyer met Phil Graham.

“I’m going to marry you.” Those were Graham’s first words to Katherine Meyer.

He then assured her that he didn’t want her daddy’s money and that he intended to carry her off to a houseboat in Florida, from which he would launch his career in politics.

She was charmed. One month later they were married.

Graham served the government during the war and fell deeper in love with Washington. He was popular — loved even — by a vast and growing network of friends. After the war, he realized that houseboat living was far less attractive than it once had been. When his father in law offered him the job as associate publisher of the Washington Post, he leaped at it.

It meant giving up his planned political career, and that became more painful as his pals John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson began asserting themselves in the public arena.

Which is not to say Graham did not have success and skill in the newspaper business. He began to chip away at the competition by arranging a deal that allowed the Post to buy the paper he saw as his head-to-head morning competition: the Times-Herald. Graham birthed a deal whereby the number-two paper was purchased by the number-three paper. (He wasn’t worried so much about the Star, which the Post would eventually overtake.)

Thus began a decade — most of the fifties and into the sixties — when Graham made advances professionally while he deteriorated personally. He suffered from a mental illness whose scale and severity was undiagnosed.

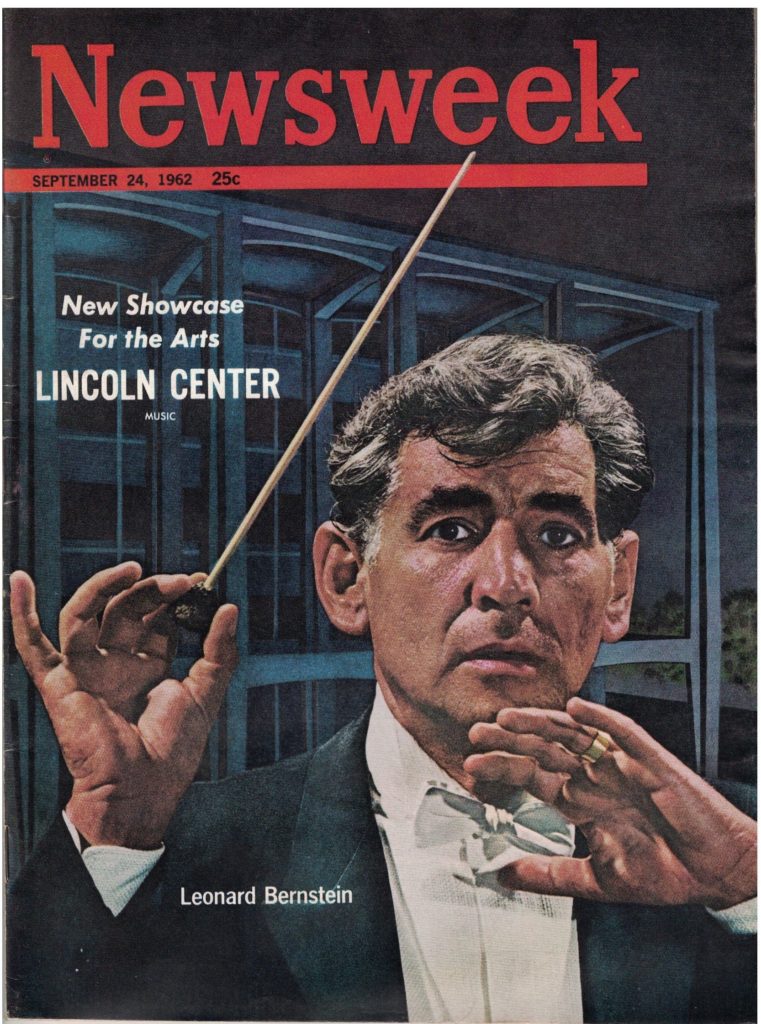

In another example of business acumen, Graham purchased Newsweek, then just an also-ran publication that was treated by the staff of Time magazine as an annoying fly.

Graham bought Newsweek for pennies and through stock-tradeoffs, and suddenly made it a legitimate competitor. (He boosted the magazine’s reputation by paying big bucks to distinguished eminence Walter Lippman. The elderly journalist lent his credibility to the magazine by writing a monthly column of political sagacity for the Newsweek masses.)

With the Los Angeles Times, Graham launched a coordinated news service to rival that of the New York Times. It was another major step in turning the Post into a world-class paper. Suddenly, the newspaper had a global presence.

But in the middle of these successes, Graham was suffering a serious mental break. Eugene Meyer died in 1959, and Graham began to speak of him in the most vile terms. He resented his father-in-law for luring him into journalism and away from politics. He also began using similar anti-Semitic slurs aimed at his children and at Kay. He publicly humiliated her by having a public affair with a young woman on the Newsweek staff.

He eventually suffered a public meltdown at a publishers’ convention in Phoenix. Graham took the podium from the scheduled speaker and assailed his colleagues. At that point, he was taken away.

John Kennedy sent a presidential plane to Arizona to bring his friend Phil back to Washington, where the publisher was committed to a private psychiatric hospital.

He appeared to be doing better. Home with Kay and his family on a weekend pass on August 3, 1963, Philip Graham killed himself with a shotgun.

Amid shocking and sudden grief, Katherine Graham was left to carry the family business forward. She was initially regarded as a pitiful figure, with industry suitors lining up to take the Post off of her hands. She made it clear that she intended to keep the paper in the family and that the next generation — son Donald was then at Harvard — would assume control of the paper.

She wanted to hand over the Post to her son in good condition. She began talking to friends, such as James Reston, Washington bureau chief of the New York Times. She discovered that although everyone had liked her husband — when he wasn’t abusive and bigoted, of course — they did not think the Post was a very good newspaper.

Kay Graham began studying her newspaper and found that she agreed with Reston. She looked around the company for someone with the vision to take the Post to the next level.

Her eyes fell on Benjamin C. Bradlee. He had come to the company with the Newsweek purchase a few years before. He was a pal of President Kennedy’s and well connected. But he also had entertained Phil and his girlfriend during the estrangement in the Graham’s marriage. Unforgivable!

When Mrs. Graham requested a lunch with Bradlee, he assumed it was to be fired. She startled him by asking what job he wanted at the Washington Post.

“Well,” Bradlee said, “If Al Friendly’s job at the Post ever came open, I’d give my left one for it.” Friendly, managing editor, was also one of Mrs. Graham’s closest friends, an ally during the horrible days of Phil’s very-public affair.

Mrs. Graham assured Bradlee that genital mutilation was not a prerequiste for the job. The editor’s job was his, and she moved her good friend, Al Friendly, out to pasture. Mrs. Graham brought Bradlee to the newspaper and within a few months had installed him as the chief news executive.

Bradlee, with Mrs. Graham’s backing, began transforming the newspaper. In those days, most newspapers, from rural gazettes to metropolitan dailies, had sections known as “women’s pages.” Bradlee sounded the death knell for that kind of journalism and inaugurated a section called Style. Pretty soon, the Post was setting the standard for newspapers trying to change with the times. The entire industry began emulating Bradlee’s style

It wasn’t until 1971, though, that Bradlee felt that he worked for a truly great newspaper. This moment of revelation came as a result of his battle for journalistic supremacy with his mortal enemy, the New York Times.

The Times had obtained a copy of a secret government-produced study of the prosecution of the Vietnam War. More than 7,000 pages in length, the study had been surreptitiously copied by one of its compilers, Daniel Ellsberg, who had become disenchanted with the war. Ellsberg leaked the documents to reporter Neil Sheehan of the Times. He digested the articles and with fellow Times reporters, began preparing articles drawn from the full study. The Times committed to publishing the complete text.

The first story of the Pentagon Papers, as the study became known, appeared on the front page of the Times on Sunday, June 13, 1971. The next day, attorney general John Mitchell obtained an injunction against the Times, forcing the newspaper to stop publishing. The government argued that publishing the Pentagon study was a breach of national security and the Times stopped serializing the mammoth report rather than risk a court battle and public scorn for being unpatriotic.

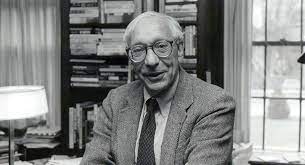

Bradlee was jealous. He was determined to get a copy of the Papers for the Post and he soon did, thanks to Ben Bagdikian, one of his editors. Soon, Bradlee set reporters to work digesting the study and began having the full report set into type.

But the Post faced two problems that hadn’t been on the table for the Times:

First, now there was a precedent. The Times had been enjoined from continuing to publish the papers on the grounds of national security. The editors there could honestly claim they didn’t believe publishing the papers was a threat, but they complied with the order. That was a precedent. The Post could not claim ignorance of the national-security issue.

Second: The Post was becoming a publicly-held company. The value of Washington Post Company stock could be seriously harmed by the newspaper publishing something that defied precedent.

Both of these arguments were presented to Katherine Graham. She considered them, and decided the Post would publish the papers. Within four days of the injunction against the Times, the Post began serializing the Pentagon Papers.

Later, Bradlee said that when Mrs. Graham made the call to go forward with the stories, he felt that he was working for a great news organization.

The federal government sought an injunction against the Post but the District Court ruled for the newspaper. By the end of the month, the case of the Post and Times was before the United States Supreme Court. The high court proclaimed that the government had not met the burden of offering sufficient reasons to deny publication. The Post emerged from the government standoff with an enhanced reputation and the stock did not suffer.

And now, almost exactly a year after the Post began printing the Pentagon Papers on its front page, the Post had found another story that would affect its reputation and role in American journalism.

. . . . . . . .

News of the Watergate break-in traveled through the Washington Post’s editorial food chain. It began with an early morning call from Joseph Califano. He was the Post’s lawyer, but he also represented the Democratic National Committee. When he got the call about the burglary, Califano tried to phone Bradlee, but the editor was vacationing in a West Virginia cabin and was unreachable. Califano then called the paper’s managing editor, Howard Simons.

Simons was interested. Though there was a political element to the story, all of the paper’s key political journalists were caught up covering the presidential campaigns and preparing to report the upcoming conventions.

Simons knew this story was best suited for the Metro section, so he called Harry Rosenfeld.

Saturday morning calls from Howard Simons were routine for Rosenfeld. This call came early, but Simons had already decided there were two stories Rosenfeld needed to pursue for the Sunday paper: the Watergate break-in and a strange automobile accident. A car had slammed into a house in a Virginia suburb, interrupting the homeowners as they performed the act of physical love.

“Talk about coitus interruptus,” Rosenfeld said.

They chatted briefly and Rosenfeld, the metropolitan editor, began mapping out his ideas for the Sunday Metro section. Most Saturdays, Rosenfeld spent a few hours at the office. Those few weekend hours allowed him to catch up on paperwork, check out the pre-printed Sunday sections, and keep an eye on the Sunday Metro section as it developed. But this Saturday, he and his wife, Anne, were having a dinner party. Leave the house and he was a dead man. So he had to turn the story over to the next editor in the food chain.

At 8:30 am, approximately six hours after the burglars were surprised by the plainclothes officers, Rosenfeld called Barry Sussman. As the editor responsible for coverage of the District of Columbia, Sussman had a 40-person staff, and worked closely with Rosenfeld. Even though he was still in bed, he tried to muster coherence for conversation.

Rosenfeld recounted what details he knew, the things that had piqued his interest in the story: first of all, the locale. It was a presidential election year, so political intrigue was always a good story. Then the clothing: what was up with the business suits? And surgical gloves? That was another strange thing. Rosenfeld wanted Sussman to get his staff moving on the story. He and Sussman agreed who should handle the reporting, then he hung up.

Still in bed, Sussman called two reporters and asked them to come in on their day off.

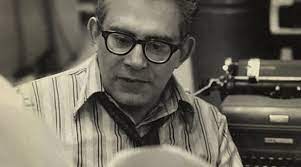

The first call was to Alfred Lewis. Sussman and Rosenfeld readily agreed he was perfect for this story. He was an anomaly on the newspaper’s staff — older than most of the rank and file reporters in the newsroom and not gifted as a probing interrogator of sources. But he was an astounding legman, fabled for his ability to amass details. He’d been with the Post for 36 years and was almost as much a cop as a journalist. Bradlee said Lewis “loved cops more than civilians.” Indeed, at the Watergate the morning of June 17, he walked past all of the other reporters in the company of the district’s police chief. He was the only journalist allowed in the Democratic National Headquarters and he was thus privy to more information than other reporters. He was a journalist blessed with the eye and the access of a cop.

But he was a journalist. Bradlee said Lewis “spent all day behind the police lines, calling into the city desk regularly with all the vital statistics.” He stayed at the Watergate all day, breaking occasionally to call Sussman with updates. Because he was pals with so many cops, Lewis claimed a desk in the secretarial bullpen of the Democratic Headquarters and sat there, observing police as they investigated. All of the other reporters were outside; no one had access like Lewis.

By late morning, Lewis called Sussman and told him there was a lot about this burglary that was out of the ordinary. First, the business suits and surgical gloves.

And then: “These guys were professionals. They had tear-gas press in their lapel pockets but no other weapons. They had cameras and lots of film, and they gave the police false names. They must’ve had an accomplice who escaped.”

“Why do you say somebody escaped?” Sussman asked.

“Because they had a walkie talkie,” Lewis said. “And when they were arrested none of them made any phone calls. But a lawyer showed up for them at the Second District. Who told him to?”

Lewis noted a few other oddities. The burglars carried significant amounts of cash and police had seized the possessions of some of the burglars, including notebooks with cryptic but eventually helpful information.

Because of his quasi-cop status, Lewis was an outlier as a journalist, but he acquitted himself heroically that day. Sussman was glad he convinced him to work on his day off.

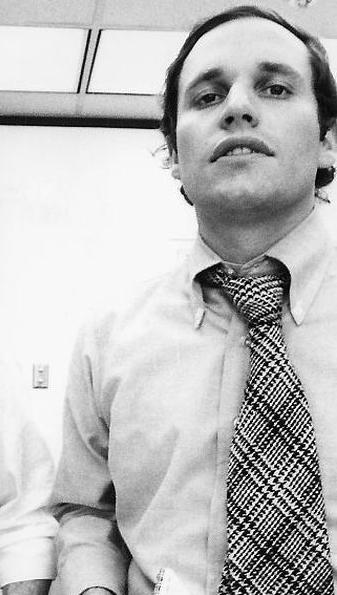

The other reporter Sussman called was the new guy, Bob Woodward.

. . . . . . . . .

Woodward was a newsroom anomaly of a different sort. At a time when journalists were either leftover blue-collar working stiffs or snot-nosed graduates of some state-college journalism school, he was neither. Woodward was a Yalie. At Yale University, Woodward studied history and English literature, and also served in the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). He graduated in 1965, then served five years in the Navy, and was discharged in August 1970. He was accepted to Harvard Law School, but instead of moving to Cambridge and enrolling, he banked the acceptance and took some courses at George Washington University. The classes were for his pleasure, just things that interested him: a course in Shakespeare and another class in international relations.

Somewhere, during this intellectual sojourn, he decided to become a journalist.

Becoming a reporter seemed unlikely, because Woodward didn’t fit the profile. In the early seventies, members of the press were long-haired, generally liberal, and fervently anti-war. Woodward was, in the parlance of the time, a straight. Chalmers Roberts, one of the lions of the newsroom, huffed, “Woodward was a nattily dressed square.” He also was a registered Republican, as rare in a newsroom as frost on a frying pan. And more! Woodward was an awkward writer at a time when journalists were supposed to aspire to the effervescent verbal gymnastics of Tom Wolfe or Hunter S. Thompson.

But he wanted to be a journalist and so he applied at the Washington Post in 1970. Rosenfeld agreed to interview Woodward because one of his bosses asked him to. Paul Ignatius was president of the Washington Post and had served as secretary of the Navy, which is where he’d gotten to know Woodward. He obviously thought a lot of the kid, who’d held a top-secret security clearance during his time in the Navy. Out of courtesy, Harry Rosenfeld gave him an audience.

Rosenfeld wondered: How do you tell someone that the Post wasn’t where you started your career; it was where you ended your career.

Woodward impressed, though, with his earnestness. “I quickly realized Woodward had a sober personality and was a solid adult,” Rosenfeld recalled. Considering the long-haired job applicants he regularly met, Woodward was unusual. He really had no experience but because of Ignatius and just because he liked the guy, Rosenfeld did something he’d never done. “I gave him a two-week tryout. This was not customary for the good reason that there is little to be learned about a novice cast as a reporter into an unfamiliar sea. I thought I owed it to Ignatius and to Bob’s singular naval background to give him a shot.”

Rosenfeld told his deputy editor, Andrew Barnes, to give Woodward an unpaid position covering the suburbs. Woodward wrote 17 stories during his tryout but not a single word of his made it into the Washington Post. Rosenfeld asked Barnes for a report on Woodward. He’s a good guy, Barnes said, but he’ll never make it as a reporter. Barnes said he thought that Woodward was hopeless — “inept at our craft,” as Rosenfeld recalled the assessment. It would take too much time for someone on the staff to train him. “I decided that Woodward needed time to age in the barrel in order to soak up the practices of newspapering,” Rosenfeld said.

Woodward was visibly deflated when Rosenfeld told him he would not last beyond the tryout period. The editor threw him a bone, offering to make a call on Woodward’s behalf to the Montgomery County Sentinel, in the outside-the beltway suburb of Rockville, Maryland. Get some experience, Rosenfeld told him, and then we can talk. “As a courtesy,” Rosenfeld recalled, “I told Woodward to keep in touch and that we would reevaluate him after a year or so.”

Woodward was depressed, but Rosenfeld’s final words, though slim on encouragement, contained at least some kind of hope to which Woodward could cling.

Get some experience and then we can talk. That wasn’t an out-and-out no. Now, Woodward realized, he had the taste for reporting.

“In failing for two weeks at journalism,” he said, “I knew I loved it.”

Woodward slunk off to the Sentinel and began work covering local government, occasionally beating the Post on a suburban story — small potatoes, but potatoes nonetheless.

That’s when the phone calls began. Like herpes, Woodward refused to go away. He was always there, on the phone.

Hi, Mr. Rosenfeld. This is Bob Woodward . . . .

Always calling, always asking if there was a job at the Post. He was tireless. Persistence, thy name is Woodward.

For months the biweekly calls went on. Rosenfeld gently told the nice young man that he still needed aging in that barrel. “I kept putting him off,” Rosenfeld said, “since I wanted him to continue to sand down his rough edges on somebody else’s payroll.”

And then one day, when Woodward called, he learned that Rosenfeld was out of the office. So he called him at home.

It was summer day, muggy and hot. Rosenfeld’s daughter, Amy, would celebrate her bat mitzvah that fall and her mother decided that the catered lunch following the rite would be held in the basement of the Rosenfeld home. It was the only place in the house large enough to hold the anticipated guests. The room was somewhat dingy from several years of living, so it was time to spruce it up. Anne Rosenfeld told her husband he would use his days off painting the basement.

Rosenfeld was on a ladder in the basement, painting the walls. Glasses splattered, latex coagulating.

Upstairs the phone rang. He heard his wife murmur answer, then her steps to the basement door. Anne Rosenfeld called down, summoning her husband to the phone.

Rosenfeld wiped the paint from his hands, stepped down from the ladder. He wiped the speckles of paint from his glasses and trudged upstairs to the phone.

Hi, Mr. Rosenfeld. This is Bob Woodward . . . .

An explosion of frustration burst forth. “I curtly told him to get in touch with me when I returned to the office,” Rosenfeld said. Hot, uncomfortable and angry, Rosenfeld hung up the phone.

Anne heard only her husband’s side of the conversation, so she wanted to know the back story. “I told her how this young guy was pestering me for a job,” he said.

Pause. Then Anne Rosenfeld said, “Isn’t this just the kind of reporter you always say you want to hire?”

She was right. Rosenfeld called Woodward back and told him he had a job at the Washington Post, starting after Labor Day.

Now, nearly a year later, Woodward was on the crest of 30, and at the bottom of the Post’s newsroom totem pole. He was unhip and an inelegant writer, but no one in the newsroom could say he wasn’t dogged. He worked so hard that people accused him of having ambition. Someone told Donald Graham, Katherine Graham’s son and the publisher in waiting, that Woodward was working so hard that someday he would be managing editor. That’ll never happen, Graham said. He’ll work himself to death before then. In Rosenfeld’s assessment, Woodward quickly developed into a good reporter, “sharper than most and more ambitious and hard-working as any.”

When Woodward came to the Post full time in the fall of 1971, he was first assigned to cover the suburbs. He was proud of a series he’d developed about filthy code-violating restaurants and small-town cop corruption. He was an artist of massaging sources. When he covered the local police, he never failed to show up at the station with enough copies of the Post and cups of coffee for everyone on duty. He risked a contempt charge and jail for refusing to reveal a source’s identity, a gutsy move for a guy so new to the business. As the first summer of Watergate began, he’d just done a series on Arthur Bremer, the failed assassin of the former Alabama governor, George Wallace, who was running for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Eager to impress, Woodward liked to come in on Saturdays to see if there was anything he could do. He came in that Saturday — June 17, 1972 — at Sussman’s behest, under the impression that the burglary was at the local Democratic headquarters. Woodward went to his desk in the cavernous newsroom and began making phone calls, trying to find out what had happened at the Watergate.

Sussman was like a conductor, managing nine reporters on the story, He asked Lewis to stay with the police as long as he could. Lewis said the burglars had a preliminary hearing in court that afternoon and Sussman asked Woodward to cover it.

Woodward had worked at the courthouse before, so he knew to approach the gaggle of attorneys gathered outside the courtroom. These were the lawyers who usually agitated for government work, representing those who could not afford their own counsel. Woodward approached them to see who was representing the burglars from the Watergate. Turns out none of them were. The burglars had their own lawyers.

Odd, Woodward thought.

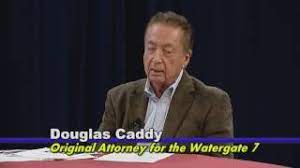

Inside the courtroom, Woodward approached a well-dressed young man who appeared to have wandered in from a country club. Woodward asked if he was representing the burglars. No, the man said, but he introduced Woodward to the lawyer sitting next to him. From Joseph Rafferty Woodward got the names and addresses of the five men. Four of them listed Miami addresses.

As he waited for the burglars’ appearance before the judge, Woodward barnacled himself to the country-club man, who turned out to be an attorney named Douglas Caddy. Like a teething puppy with a sock, Woodward was relentless, following Caddy wherever he went in the courthouse. They did a hallway-to-courtroom-to-hallway dance as the judge dispatched other routine cases.

With each question he tried to evade, Caddy nonetheless left a squib of information that Woodward picked up. Finally, Caddy admitted that he had met one of the burglars, Bernard Barker, at a cocktail party and that he had gotten a call at three in the morning from Barker’s wife. Her husband had told her that if he didn’t make it home by 3 am to give Caddy a call.

Odd again, Woodward thought. How does Mr. County Club come to know a burglar? And if they met only once, why would he be the guy to call at three in the morning?

The burglars filed into the courtroom around three-thirty that afternoon. They took their seats. Woodward was behind the bar, in the first row of the gallery.

The judge, James Belsen, asked the five men to state their professions. “Anti-Communists,” one of them said.

Judge Belsen appeared unsatisfied by that answer. He beckoned for the tallest of them to stand and state his name and occupation. McCord gave his name, then said he was a security consultant.

Where, the judge asked. McCord said he had recently retired, but had worked for the government.

Again, the judge: where?

“The CIA,” McCord said. If Woodward had not been sitting in the front row, he might not have heard it.

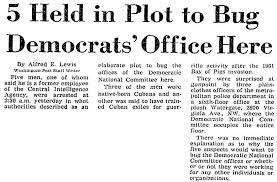

The next morning, the Post ran a front page story under the headline “5 Held in Plot to Bug Democrats’ Office Here.” Alfred Lewis got the sole byline, though Woodward was one of eight members of the staff to contribute to the story. One of the other reporters who contributed to the piece was Carl Bernstein.

Woodward thought there was something odd about this story. He looked over the fabric of the incident: burglars in business suits, rubber gloves, cash, attorneys who appeared without being called, walkie talkies, the mysterious accomplice.

As he thought about it all, Woodward’s diligent mind began to pull at the threads of the fabric to see what unraveled.