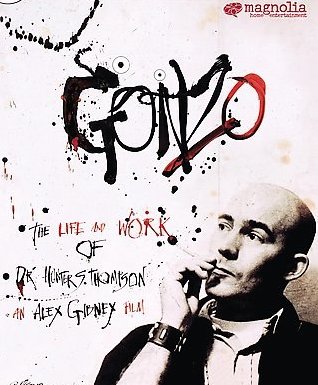

Gonzo: A History

by William McKeen

Copyright © 2023

Gonzo journalism was a term coined to describe the writing of Hunter S. Thompson and is probably best described as whatever Thompson produced. The term came into common use, however, so it’s worth a definition.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Thompson struggled to write a book for which he was contracted with Random House. The subject, as defined by Thompson, was the death of the American Dream. He made many attempts over several years, but was unable to wrestle that ponderous topic between covers. In the late 1960s, he ended up accepting magazine assignments that might produce articles that, when assembled, could – tangentially, at least — address the subject he had in mind.

One such assignment came from Playboy in 1969. He was assigned to profile the French Olympic skier, Jean-Claude Killy. Killy, portrayed in the mainstream press as a handsome French rake, was working as a pitchman for Chevrolet in a new series of television commercials. Playboy assigned Thompson to write a by-the-numbers profile of the new romantic athlete, with the ulterior motive of getting Chevrolet advertising.

As he began trailing his subject through the Chicago Auto Show, it soon became clear to Thompson that Killy had an all-embracing disdain for American cars. Thompson also found him quite tedious. At one point, Thompson confronted Killy with his problem as a writer. It was grueling, he told his subject, to write about Killy because the man was so monstrously dull. Killy shrugged. “Maybe you could write about how hard it is to write about me,” he said.

And that was it. Thompson was thus handed the prescription for the rest of his career. He inaugurated his practice of writing stories about Hunter Thompson trying to write stories. No matter the assignment, he wrote about his difficulties trying to write a story.

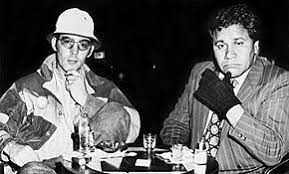

He completed the story on Killy, using another journalist – Bill Cardoso of the Boston Globe – as a confederate. Thus began the Thompson literary device of employing a sidekick as a sounding board. He used Cardoso to vent his frustration and to share his ideas about trying to write a story about a staggeringly boring man.

Playboy aggressively rejected the article because Thompson reported Killy’s scorn for Chevrolet. Any hope of advertising would evaporate with the story as written. Thompson was furious and wrote to his friend Warren Hinckle, then publishing a magazine called Scanlan’s Monthly. Thompson spewed his bile for Playboy and enclosed the manuscript with the letter to Hinckle. Both letter and article were printed in the next issue of Scanlan’s, including Thompson’s reference to the Playboy editors as “scurvy fist-fuckers to the last man.”

“The Temptations of Jean-Claude Killy” marked the beginning of a turning point in Thompson’s career.

For his next Scanlan’s assignment, Thompson was paired with Welsh illustrator Ralph Steadman, who was making his first trip to the United States. Hinckle sent Thompson back to his hometown of Louisville, to cover the Kentucky Derby. It was a righteous pairing, as Thompson used Steadman-as-sidekick to explain what sorts of pictures fresh-off-the-boat Steadman needed to draw to accompany the article that he – Thompson – was having such difficulty writing.

And it was difficult. As Thompson assembled the article on deadline, he began passing unedited sheets torn from his reporter’s notepad to the Scanlan’s editors and discovered that they planned to print them verbatim in the magazine. When “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” appeared in May 1970, Thompson figured his career was over. Publishing such insane ramblings was, he figured, a crime against journalism. Instead, his mailbox was soon stuffed with letters of admiration from colleagues who referred to the piece as the next step in the evolution of journalism.

Bill Cardoso sent him a note. “I don’t know what the fuck you’re doing,” he wrote, “but you’ve changed everything It’s totally gonzo.”

Cardoso was using the Boston-bar definition of the word. “Gonzo” was local pub slang for the last one standing after a night of drinking. The word might have appealed to Thompson because in his days at Eglin Air Force Base in the Florida Panhandle, he’d listen to WWL from New Orleans late at night, where the disk jockeys regularly played the instrumental “Gonzo” by James Booker.

Whatever the source of the word – and there is a French Canadian gonzeaux — it soon became the catchphrase for whatever Thompson wrote. The question became this: was gonzo the sole intellectual property of Hunter S. Thompson?

There had been antecedents. Writer Terry Southern had experimented with this metajournalism when he wrote “Twirling at Ole Miss” for Esquire in July 1962. Sent to Oxford, Mississippi, to cover a baton-twirling summer camp, Southern spent his article describing the difficulty of writing his article – primarily because, in a monument to political incorrectness, he could not concentrate because of the lust he felt for his adolescent subjects. It was an article about the difficulty of writing an article.

When “Twirling at Ole Miss” was printed, Thompson was an obscure American freelance lobbing stories stateside from remote outposts in South America. No one called Southern’s work gonzo, though it fit the later definition of metajournalism.

After Thompson embraced Cardoso’s term, it became too closely associated with Thompson to be successfully appropriated by other writers. Thompson’s device worked well in the book-length Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Random House, 1972), in which he wrote about trying and failing to produce articles on two events in that city. Thompson then spent a year covering the battle for the presidency between incumbent Richard Nixon and challenger George McGovern. Thompson’s biweekly articles in Rolling Stone watered and manured his image as a man in constant struggle to meet deadlines. The process of writing was the subject of his writing. Those reports were later collected as Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 (Straight Arrow, 1973).

Those attempting to write in his style realized what an ill-fitting suit of clothes it was. Only one person could write like that.

Despite that, many tried. Writers around the globe attempted to establish new strains of gonzo. Even in the United States, and in his home turf at Rolling Stone, writers were tagged as new practitioners of gonzo. We speak of P.J. O’Rourke and Matt Taibbi. Fortunately, their originality was soon recognized and the comparisons stopped.

Gonzo died with Thompson’s suicide in 2005.

It remains a widely used term with a narrow definition.

NOTES

- “Maybe you could write about how hard it is to write about me.” Hunter S. Thompson, The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time (New York: Summit, 1979), p. 90.

- “scurvy fist-fuckers” Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000), p. 223.

- “I don’t know what the fuck you’re doing” E. Jean Carroll, Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson (New York: Dutton, 1993), p. 124.

FURTHER READING

- Carroll, E. Jean. Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson (New York: Dutton, 1993)

- Denevi, Timothy, Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism (New York: Public Affairs, 2018)

- Feehan, Rory. The Genesis of the Hunter Figure: A Study of the Dialectic between the Biographical and the Aesthetic in the Early Writings of Hunter S. Thompson (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Mary Immaculate College, 2018)

- McKeen, William. Outlaw Journalist: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson (New York: Norton, 2008)

- Southern, Terry. Red Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes (New York: New American Library, 1967)

- Thompson, Hunter S., The Great Shark Hunt: Strange Tales from a Strange Time (New York: Summit Books, 1979)

- ______. Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000)

- Wenner, Jann, and Corey Seymour. Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson (Boston: Little Brown, 2007)

- Wolfe, Tom. The New Journalism (New York: Harper and Row, 1973)