The Alternate Take

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times, 2006

Imagine Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas without pictures. It’s hard. Hunter Thompson’s words still rip flesh and achieve supersonic velocity. But is the book the same without those wicked pictures of two men making beasts of themselves in the city of sin?

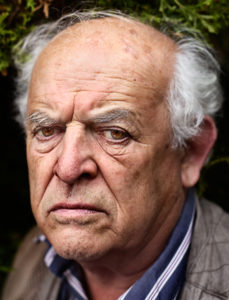

Probably not. Ralph Steadman’s magnificently twisted vision is part of the Gonzo DNA. His characters are often part skeleton, part human and part reptile and perfectly matched to Thompson’s often disturbing and hallucinogenic vision.

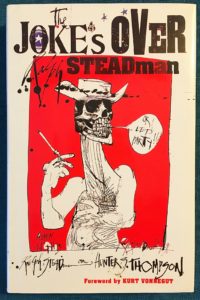

Thompson committed suicide early last year and it seems that half the free world is writing a book about him. Few will be as honest – and necessary to understanding the author – than Steadman’s memoir, The Joke’s Over. Their collaboration lasted 35 years and Steadman writes with searing honesty of his complex relationship with the brilliant and monumentally flawed author.

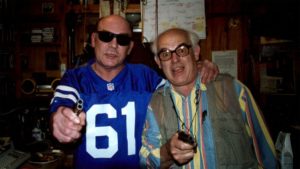

They met on a magazine assignment in 1970. Thompson was heading back to his hometown, Louisville, ostensibly to cover the Kentucky Derby, but mostly to check in on what was happening to the heartland in the era of Richard Nixon. He had heard about Steadman, a Welsh artist who had just set foot in America for the first time, and he urged the editor to call him.

The assignment came so quickly that Steadman didn’t have a chance to round up his usual artist tools. Using borrowed lipstick and mascara pencils, Steadman and his drawing pad followed Thompson through Churchill Downs looking for the face of modern American depravity that the author promised. Thompson vowed the face would be bloated and booze-ravaged, full of horror and bile. They finally find the face, of course, when Thompson looked in the mirror after the race.

Though ostensibly about the spectacle of the Kentucky Derby, the horse race played a minor off-camera role in Thompson’s story. In fact, he ended up writing the story about trying to write the story. Under deadline pressure, he ripped pages from his notebook and sent his scrawl off to the magazine in the ancestor of a fax machine. Afterward, he was convinced he would never work again for a major magazine. He also thought Steadman’s drawings would be too repulsive for publication.

He was, of course, wrong. The resulting article, “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved,” was Thompson’s breakthrough and earned his style of writing the name “gonzo.” It appeared in a soon-to-be-defunct magazine called Scanlan’s, but the Thompson-Steadman team was soon picked up by Jann Wenner for his fledgling magazine, Rolling Stone. Thompson’s rants were the highlights of the magazine in those years and whether Steadman was along for the ride or not – most often, not – his drawings perfectly matched Thompson’s bizarre and self-indulgent form of journalism.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas originally appeared in Rolling Stone in 1971 and in book form a year later. Steadman was definitely not along for that wild ride; Thompson’s companion for his mad-dog romp through Vegas was flamboyant Chicano attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta. But Steadman had been there – there being with Hunter Thompson on other crazed trips – and he had enough mind-altered memories stored to illustrate a hundred books.

Reading Steadman’s memoir is like hearing an alternate take of a classic rock song. It has all of the essential elements, yet it’s unfamiliar. Steadman’s version of the Derby story is more straight-forward, and his accounts of their other adventures covering the America’s Cup or the political conventions are lucid, alternate histories.

Steadman’s book is much more insightful that many of the things written about Thompson – many of which turn into rambling accounts of Amazing Drug Tales. Thompson’s appetite for altered living is perhaps as celebrated as his writing. The Joke’s Over gives insight to how he worked, not just how he played.

In the process of writing the book, Steadman turned over their 35-year friendship in his hands and studied it. Sometimes, he didn’t like what he found. “When I began this book,” he says at midpoint, “I thought it was going to be a journey of pleasure and warm memories, but as I write I feel more of the icy winds of rejection that were probably there from the beginning.” Steadman had a successful career away from Thompson and had done books on God and Leonardo da Vinci and illustrated a new edition of Alice in Wonderland. Thompson comes off as utterly bored with Steadman’s other life. Theirs was an often lopsided friendship.

But Steadman still loves his friend and his account of their partnership opens a door to a part of Thompson he rarely showed in his own writing.

“Don’t write, Ralph,” Thompson once told Steadman, “You’ll bring shame on your family.” On that point, at least, Thompson was wrong.