The President in Waiting

Appeared in Creative Loafing, August 26, 2009

Ted Kennedy made a stop through Indiana during the 1972 presidential campaign and I covered the rally in Tarkington Park in Indianapolis. I was in the press section with my colleague Brian Knowlton, now with The New York Times. In addition to local government and politics, I wrote about rock’n’roll and covering those ear-blistering concerts prepared me well for that Kennedy rally. He was a political rock star.

He was there to speak on behalf of Rep. Andrew Jacobs, who was facing a tough re-election bid, and George McGovern, the presidential nominee for the Democrats.

But the crowd was there for Kennedy. He barked out a speech in staccato bursts and the crowd cheered at all of the scheduled intervals. What a pro, I thought. This dude oozes politics from his pores.

It was at the end of the speech that Brian turned to me and noted something interesting about Kennedy’s talk. He was there for McGovern, had spoken for 20 minutes about the virtues of the Democratic ticket, but had never once mentioned the candidate by name.

Truly a pro. He knew there would be a massacre at the polls and didn’t want to taint himself by even mentioning the presidential candidate. That’s the sign of a skilled politician, I thought.

That was just a few years removed from the bridge at Chappaquidick and was too soon for Kennedy to have rehabilitated himself for a presidential run. For two generations, he was the president in waiting. But it was not to be.

It was never the right time. After Watergate, the country wanted an outsider and got Jimmy Carter. The ill-fated 1980 campaign showed Kennedy had lost a step as he finished a humiliating second in his party to Carter. By the middle of the 1980s, he had lost the charisma war to Ronald Reagan and settled into his senatorial rut as the former boy wonder fading into the role of aging happy warrior.

His brothers all died suddenly, in war or by assassination. Ted Kennedy had a longer time to reconcile himself to his long decline and, eventually, to accept and face death. As the patriarch-by-default, however, it was his sad duty to preside over the tragedies and excesses of the whole Kennedy bloodline. It was the price of longevity.

The press had a fascination with that family – a lurid obsession that was the equivalent of political porn. Through the alcoholism, the Palm Beach rape, the accidents, the drugs, the drugs and the drugs, American audiences could not get enough of anything Kennedy. Ted Kennedy fought his own battles with excess but when things were at their worst, he was often at his best.

That had not always been the case. Rarely had a political life been through such a symphony of scandal. Chappaquidick would have been the end of any other politician’s career. Perhaps it should have been. But once he recovered politically, it seemed, there was a new scandal – divorce, alcoholism – to be faced down. And then another one.

In death, some tributes will call him the lost president. He was the sure thing that wasn’t.

It was a life bursting with trial and tragedy. Perhaps it was not unusual in that regard. But the spectacle for this family was played out in the tabloids and it was the sad duty of the last surviving son to hold things in line the best he could.

He retained the family’s oratorical magic. When I think of him, I’ll recall his stirring eulogy for his brother Robert in 1968, and his concession speech at the 1980 Democratic Convention. After running a brutal and somewhat mean-spirited campaign against Carter, he gave up with a speech as moving as any political speech I ever heard. Looking back, you can see it as a farewell to the old days of Kennedy politics and his public realization that he would not fulfill what those of us in the press often called the family destiny. But as a skilled politician and speechmaker, he knew how to tantalize and hold out hope. “The dream shall never die,” he said. Then he waved, stepped back from the podium, and it was all over.

. . .

Appeared in the St. Petersburg Times, October 2, 2010

“Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

That was Al Pacino’s lament in The Godfather, Part III, but it also applies to anyone who thinks they’ve read all the Kennedy books they need for a lifetime.

After the teary-eyed John and Bobby books of the Sixties, the Kennedy family epics, the historical fiction wrapped around the family’s Ireland-to-America saga, and the myth debunking (principally Seymour Hersh’s Dark Side of Camelot and a boatload of books by conservative authors), it seems that everything that could be said about America’s royal family has been said.

Burton Hersh, who has a home in St. Petersburg, has written several other books about the Kennedy family, most recently Bobby and J. Edgar: The Historic Face-Off Between the Kennedys and J. Edgar Hoover that Transformed America, published in 2008.

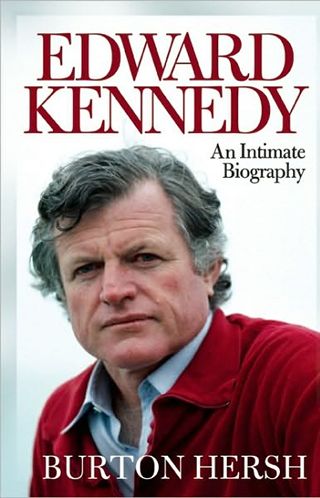

Now, a year after the last brother’s death, he has published the massive Edward Kennedy: An Intimate Biography. Weighing in at 686 pages, it might be the definitive book on the youngest member of the family, and the one who had the longest career shaping public policy.

As a reporter, Hersh covered most of that career, even before Kennedy’s election to the U.S. Senate in 1962. It was Kennedy’s nature to make friends with people he hung out with for half a century, so Hersh’s self-references here and there are a little jarring in a political biography. It was Kennedy’s nature to ask friends for advice, so it’s a step into a literary netherworld when Hersh writes about Kennedy’s solicitation of the author’s ideas on this or that political move.

But journalists or historians who became intimate family friends wrote some of the finest Kennedy books. At the beginning of the magnificent Robert Kennedy and His Times, Arthur Schlesinger said, “If it is necessary for a biographer of Robert Kennedy to regard him as evil, then I am not qualified to be his biographer.”

Hersh’s friendship with his subject does not affect the judgments he offers. Though he clearly admires Edward Kennedy, Hersh recounts Kennedy’s prolific faults. The 1969 death by drowning of Kennedy campaign worker Mary Jo Kopechne is dealt with in severe detail; nearly 50 pages are devoted to the accident and the senator’s irresponsible behavior in its aftermath.

Similarly, Hersh deals frankly with the senator’s alcoholism and indiscretions, including his failure as a patriarch to the next generation and its members’ troubles with substance abuse and sex scandals.

But reading 686 pages about a saint would be tiresome, unless the work in question is a holy book. What gives Hersh’s book resonance is that it is ultimately a story of redemption, told through the life of a dedicated and tragic public figure.

It’s one more Kennedy book that you need to read.