At the beginning of 1967, Brian Wilson was on top of the pyramid.

In the previous year, he’d made Pet Sounds, one of the most influential albums in recorded history, then produced a stunning, shimmering song called “Good Vibrations.” With Brian Wilson as producer-arranger-composer, the Beach Boys had become America’s pre-eminent rock band.

The word was that Brian Wilson was a genius and that he was to American music what Magellan was to world travel.

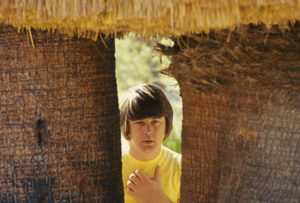

Most of this ‘genius’ speculation was based on Brian’s work-in-progress, an album to be called Smile that would serve as his “teen-age symphony to God.” Brian’s idiosyncratic music, paired with the intense and playful lyrics of Van Dyke Parks, were the stuff of rock-critic legend. Reporters chronicling the making of Smile gorged on Brian’s eccentricities, including his filling his dining room with sand, so he could move his piano into the room and wiggle his toes as he composed.

As I say: at the beginning of 1967, he was on the top of the pyramid. By the end of the year, he’d tumbled from those staggering heights.

Lots of reasons, but the one that seems to have earned the most favor over the years: The Beatles surpassed him. The British group produced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and left the Beach Boys in their stellar wake. Since Sgt. Pepper strove for — and achieved — grandiosity, Brian probably thought Smile — with its celebration of small moments of joy — might not stand up.

Whatever the case, he cancelled the album after Pepper‘s release and withdrew the band from the Monterrey International Pop Festival. Those two events are seen as crippling the Beach Boys as a significant rock’n’roll band.

(Though tragically unhip in America, they remained revered in Great Britain, where they were arguably more popular than the Beatles.)

To recover, other members of the band coaxed Brian back to life on the ground. They built a studio in Brian’s house and cocooned him, which kept him away from the great studios — Western Recorders or Gold Star — and the session players history has dubbed the Wrecking Crew.

Instead, Carl Wilson helped his big brother to make “music to cool out by.” The other members pitched in. If their musicianship was not at the level of the session pros in the Wrecking Crew, then so be it. They worked toward a simpler sound. For some reason, Brian had his piano detuned, so it sounded like the kind of thing you’d heard when friends got together in the basement after a few beers.

In place of Smile, the Beach Boys produced Smiley Smile in September 1967 and Wild Honey in December 1967. And ‘produced’ is a key word there. The earlier Beach Boys albums bore the ‘Produced by BRIAN WILSON’ credit. Now the jacket said, ‘Produced by THE BEACH BOYS.’

This music was the antithesis of Sgt. Pepper or The Notorious Byrd Brothers or anything by Jimi Hendrix (who sealed the doom of the band’s hipness with his “may you never hear surf music again” hidden lyric on “Third Stone from the Sun”). As Roger McGuinn of the Byrds said of 1967, all the artists were trying to out-weird each other.

The Beach Boys had done weird, with Smile, and found it not to be suitable.

They never tried to be something they were not. And what they were was three brothers and a cousin from the suburbs. So the heavy intellectual stuff and pomposity didn’t fit well. Years ago, a writer put it nicely. Wish I could remember his name or the correct phrasing, but it was something like “We are a confounding country. We can put a man on the moon but we can’t stop people from wearing spandex pants to the mall. The Beach Boys will drive you crazy that way too.”

In short, you’ve got to be willing to take the goofy with the great.

When Smiley Smile came out, it was largely panned, though it’s an excellent album. But since it was the ‘Instead of Smile‘ album, it was held to an impossible standard. As Carl Wilson said, “It was a bunt instead of a grand slam.”

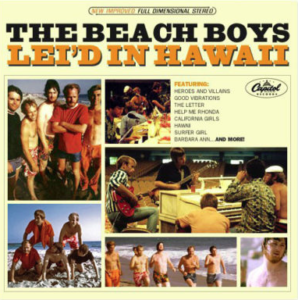

The recorded-in-the-living-room vibe gave Smiley Smile a wholly original sound. After a live album in Hawaii was discovered to have been poorly recorded, the Beach Boys took this new homegrown work ethic into a studio where they tried to fix the live album with some live-in-studio recordings. They abandoned that project and instead went back to the living room and made Wild Honey, the closest thing the group ever recorded to a rhythm and blues album.

This has always marked the beginning of my favorite period in Beach Boys music. When the mass audience and the new ruling class of rock intelligentsia looked elsewhere, the Beach Boys made music for themselves. This wonderful era is now chronicled in the two-disc history 1967: Sunshine Tomorrow (come on boys, pick a title).

What we have in Sunshine Tomorrow isn’t a collection of snippets and scraps. Producer Mark Linnett has taken these old pieces and put together a new piece of work — not just a document of a creative period in the band’s life, but something that stands up today. This is a glorious album.

Linnett sets the stage by starting with Wild Honey in a new stereo mix. He then works through some session outtakes and live performances. As brilliant as that is — and Wild Honey has some of the best Beach Boys songs ever — it’s the Smiley Smile sessions that provide some of the great delights.

Wisely, Linnett leaves off “Good Vibrations” (Brian didn’t want it on the original album anyway) and he uses the backing tracks of “Heroes and Villains,” instead of the vocal, which would have contained those wonderful but overwhelming lyrics. Linnett eases into the Smiley Smile material with revelatory backing tracks, gradually building to the wonderfully weird and stoned-out “Wind Chimes,” “Cool, Cool Water,” “Vegetables” and “Little Pad.”

From there, Linnett goes into the faux-concert album as the scaled-back homegrown Beach Boys recreate their Hawaii setlist from the poorly-taped concerts on Oahu. (Brian had come out of performing retirement to join the band on stage.) These quiet versions of “California Girls,” “Help Me Rhonda” and “Surfer Girl” are wonderful reinterpretations.

If I never hear “Surfer Girl” again, I’d be okay. But here, it’s done in a laid-back style that renders it a whole new song. Mike Love loses his usual braggadocio and “California Girls” becomes a gentle lament. (Love’s singing throughout is reserved. He pulls back on the usual swaggering bullshit and sings with tenderness.) Alan Jardine changes the perspective of “Help Me, Rhonda,” turning the story around, so it’s more of a “Help You, Rhonda” now. They sound remarkably like the Ramones doing “Beat on the Brat.”

The real surprise is the concert-in-the-studio version of “You’re So Good to Me,” from the 1965 album Summer Days. Brian Wilson’s new arrangement is much richer than the shrill chant from two years (and a lifetime) before. If only the music business still revolved around singles, this would be a good one.

The group also does some then-current songs by other groups: “With A Little Help From My Friends,” “The Letter” and “Game of Love.” The combined Carl-Brian-Mike shared lead vocal on “The Letter” is particularly fun. (By the way, the set ends with a thrilling a cappella “Surfer Girl.”)

This was a great period for the group and to hear them and marks Carl Wilson’s emergence. Though in retrospect we can see he had the best solo voice, he was not eager to sing lead vocals. He carried “Pom Pom Play Girl,” but it was “Girl, Don’t Tell Me” from 1965 that he considered his first lead. Then big brother entrusted him with “God Only Knows” and “Good Vibrations.” If that doesn’t demonstrate trust and respect, I’ll eat my Volkswagen.

Carl is all over Wild Honey and his love of rhythm and blues comes out in his unrestrained, fluid vocals. He does a tremendous cover of Stevie Wonder’s “I Was Made to Love Her” (listen for the you-son-of-a-bitch hidden lyric) and “Darlin'” is irresistible.

As McGuinn said, everyone was trying to out-weird each other, but the Beach Boys were hanging out in Brian’s living room, singing rhythm and blues around that deliberately detuned piano. The slightly off sound of the music — and the overall dominance of the piano — gives the music of this era a resonance.

Who knew that the Beach Boys would be the harbingers of what would start happening that very month Wild Honey was released.

Tired of the grandiose bullshit (he thought Sgt. Pepper was a piece of crap), Bob Dylan came out of his 18-month seclusion and produced the quiet masterpiece, John Wesley Harding. It was Dylan’s way of grabbing rock’n’roll by the lapels and saying, “Pull yourself together!”

Soon, the Beatles were cutting out all of the studio gimmickry and promising to ‘get back.’ Meanwhile, the Byrds and the Band were discovering what today we call roots music and Americana.

In a way, the Beach Boys were there first.

My old-man bias is that this period – 66/68 – was the high-water mark when music matter most to culture.. and yeah, we’ve had moments and bands since then, but they’ve not reached that height.. Dylan, the Beach Boys, the Beatles, even the Stones.. I saw the Stones in early 67 (immediately after the drug busts and before the trials) and, a year, later the Jimi Hendrix Experience.. it’s nearly impossible to understand now the sense that it was all coming apart and that these bands understood that & were partially responsible..