The Ultimate Freelancer

This essay is part of Eric Shoaf’s Gonzology: A Hunter S. Thompson Bibliography (Cielo, 2018).

He must’ve known. From the time he was a child — a teenager, at least — Hunter S. Thompson thoroughly documented his life. He kept carbon copies of his letters in boxes, along with pictures, notes, audio recordings, peacock feathers, and other tactile evidence of his time on earth.

He must’ve known not only that these things would matter one day, but that these things would matter to us, the legions of readers who admired his eyes on our world and loved the electric cadence of his prose.

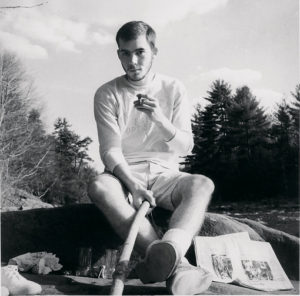

Even in his solitude more than a half-century ago, as a hungry, unemployed Air Force veteran living in an unheated cabin in upstate New York — even then, with ambition but no serious publications, he felt the need to set the timer on his camera and document his life.

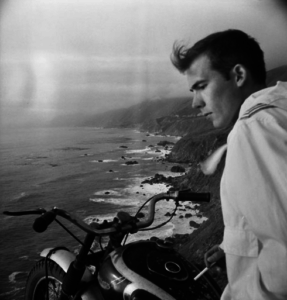

So we see him there, bearded, looking very writerly, outside the cabin near Cuddebackville. And there he is, hairy and looking with fright into the bathroom mirror. And again: the junior varsity man of letters, smoking insouciently in a weathered easy chair in his New York City apartment. At Big Sur, he leaves himself out of the photograph, and preserves the image of his writing table at sunset. There it is, overlooking the pockmarks of the rocky coast. But it says, “I work here at the end of the world. Welcome to my paradise.”

If he was full of promise, it was visible only to himself and not to others. Still, he had that dedication, and vowed that until the dark thumb of fate ground him into dust, he would be a writer.

In 1967, he wrote a remembrance of his colleague, Lionel Olay, for a microscopic magazine, titling his tribute “The Ultimate Freelancer.” But that was Hunter S. Thompson. In those early days, whether he was in the freezing cabin or on a smuggler’s boat in South America or the Big Sur paradise, he took whatever assignment he could draw, writing most waking moments of his life.

He left behind the scattershot publications of a struggling hand-to-mouth writer. Eventually, this insatiable hunger for assignments led to better and better markets. Fortunately, his gift for correspondence and his desire to converse and confound, he found editors who recognized his gifts.

First came Clifford Ridley of the National Observer, who saw the juice in Hunter’s letters that accompanied his postage-paid dispatches sent from South America. Then came Carey McWilliams of The Nation, whose guidance led Hunter to write Hell’s Angels. Warren Hinckle recognized Hunter’s unique voice and gave him space to see it himself in Scanlan’s Monthly.

And then there was Jann Wenner. Hunter’s relationship with the Rolling Stone editor was complex and difficult, but the result benefited the both of them with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and the groundbreaking coverage of an American presidential campaign.

So when we look back now on Hunter S. Thompson’s 67 years on earth, we have a rich collection of writing. After years of silence and cocaine in the late seventies and early eighties, he came roaring back with several books during the back nine of his life, becoming, in his way, prolific.

Those early selfies from the cold cabin and the fleabag apartment freckle the pages of his wonderful collections of letters, The Proud Highway and Fear and Loathing in America, as well as his autobiographical collages, such as Songs of the Doomed and Kingdom of Fear.

Beyond the books, of course, he left 800 much-discussed crates of unpublished writing, copies of his obscure publications, photographs of empty rooms and, of course, peacock feathers. Always peacock feathers.

We have here a tribute to a life documented and relished that offers clues to existence on the American Earth during the times of Hunter S. Thompson. There are no sacred scrolls here (profane scrolls if any kind), but there is no denying our astonishment with this epic chronicle of one man’s life and his observations on the meaning of that life.

Eric Shoaf’s bibliography evidences the crossroads of a writer’s life and art. Here we have not just a listing of his major publications and their vagarities, but a treasure charting the trajectory of a life. These include his earliest work for Louisville’s Athenaeum Literary Association, through his “Spectator” columns for the Command Courier at Eglin Air Force Base, through his later better-known — though often, no less scattered — work. Included are quotes, blurbs, one-off comments and the like, all the way up to his incisive interviews, which often read like beat poetry and serve as his unwitting contribution to the realm of spoken-word performance.

If ever a writer blurred the lines between life and art, it was Hunter S. Thompson. He left a record that Shoaf has assembled from scattered clues hiding in plain sight. We are lucky to have this thoroughly dissected view of a strange and savage — and important — life.