Watching the Animals at the Zoo

Appeared in Creative Loafing, July 15, 2010

Summers — when I was a kid, growing up in Fort Worth, Texas — my mother used to drive me to Trinity Park every Thursday morning and leave me there for the day.

Summers — when I was a kid, growing up in Fort Worth, Texas — my mother used to drive me to Trinity Park every Thursday morning and leave me there for the day.

I was 10. Today, she’d be arrested for child neglect. But it was a different world then, and a gang of us gathered there every Thursday for all the wonders Trinity had to offer: a roaring creek for our homemade skiffs, a small amusement park with bumper cars and the mysteries of the Fort Worth Zoo.

Admission to the zoo was free — odd, that — so each week I’d take a stroll through the canopy of oaks under which the animal displays were nested.

Lions, tigers and bears… And elephants and gorillas… and giraffes, too.

I was drawn there every week, despite the fact that the visits depressed me. The animals always looked so monumentally bored. To my self-conscious 10-year-old’s mind, they seemed embarrassed at being on display. I could understand their humiliation. Like all kids, I hated people looking at me.

So I’d head off to the bumper cars.

I haven’t spent a lot of time at zoos since. Perhaps I should be recalled to the father factory to fix this defect. In 30 years of parenthood, I’ve taken children to zoos rarely and to a circus only once.

The concept of caging an animal for our perverse viewing pleasure seems wrong. Yet I rarely see a giraffe in my neighborhood, so how would I be able to appreciate the awkward magnificence of that animal without seeing it on display?

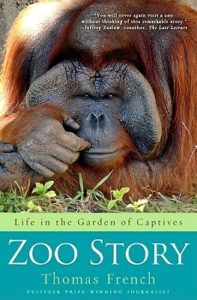

Zoos are by definition morally ambiguous, and I’m not sure I realized how I felt about them until I read Thomas French’s excellent new book, Zoo Story(Hyperion, $24.99). French spent most of the last decade reporting on life at Tampa’s Lowry Park Zoo, and has produced this thrilling, fascinating book.

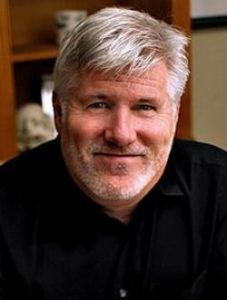

French won a Pulitzer Prize during his 30 years with the St. Petersburg Times. He became known as one of the nation’s most skillful writers of non-fiction narratives.

His first book, Unanswered Cries (St. Martin’s Paperbacks, $7.99), grew from a series he wrote for the paper about a Gulfport neighborhood’s indifference when a woman was murdered at her front door.

He spent a year inside Largo High School and produced the remarkable 1991 Times series that later became the book South of Heaven (Simon and Schuster, $12). That book showed one of French’s greatest gifts: his ability to write so achingly about the pangs of adolescence.

One of the high school students who shared airspace with French during that year was Greg Hardy, who now works for CBS Sports. Seeing French at work altered the course of Hardy’s life, and led to him becoming a journalist. (If not for meeting French, Hardy figures he might’ve fulfilled his 17-year-old ambition to be a comic-book penciler.)

Twenty years later, Hardy is still awed by how French reported on the drama of teenage life and the choices he made in telling the story.

“Think about it: If he tells us every single thing he saw in every class every day, it’d be worse than listening to that boring history teacher whose class you were trapped in while French sat behind you, scribbling his notes,” Hardy said. “You’re talking ‘Dear diary’ or phone-book territory. French knows the three most powerful words in writing are ‘Tune in tomorrow.'”

French explored similar territory with his “13” series for the Times and again showed a unique ability to crawl inside the adolescent mind.

He earned his Pulitzer for “Angels and Demons,” the story of a multiple murder and its aftermath — the killing of a mother and two daughters visiting Tampa Bay from Ohio. When the story runs its course with the execution of the convicted killer, I hope French will preserve that tremendous work of journalism in book form.

So at first a story about zoo animals doesn’t seem to fit the French profile. Here’s a guy who writes so evocatively about tortured young people and the haunted survivors of brutal crime.

What’s the deal with the animals?

In 2003, French read Yann Matel’s Life of Pi and was moved by a passage about the limits on freedom, both in nature and inside the walls of a zoo. He went to Lowry Park and asked for permission to report on the lives there — animal and human.

As a reporter, French has influenced a generation of journalists, providing a role model of obsessive reporting and sensitive writing. He’s also developed a reputation as a bit of a stonecutter — that is, his storytelling takes time.

At the zoo, he became fixated on this whole new world of animals — and those who care for them.

For six years, the zoo was his life. He saw the zoo’s problems, the changing of the executive guard and the threats of disruption by animal-rights groups.

But telling the story required much more than hanging out at Lowry Park. The story also took him to Africa, where he saw the way in which animals are acquired for zoos.

In writing the series that became Unanswered Cries and “Angels and Demons,” French had shown himself to be a single-minded reporter, concerned with justice for the victims of atrocities.

Now, for much of the last decade, he was applying the same grueling reporting regimen at Lowry Park. Some at the Times just shrugged.

“Some colleagues in the newsroom definitely wondered if I was wasting my time,” French said. “‘It’s just a bunch of cute animals,’ they said. ‘What could be happening that was so interesting?'”

“Some colleagues in the newsroom definitely wondered if I was wasting my time,” French said. “‘It’s just a bunch of cute animals,’ they said. ‘What could be happening that was so interesting?'”

Everything, French told them.

The zoo had it all: “Life and death. Power. Betrayal. Sex — lots and lots of sex. The fight against global extinction. Not to mention the fact that many of the animals turned out to be some of the most interesting individuals I’d ever reported on.”

Few writers tell human stories with the sensitivity French brings to Zoo Story. Perhaps his most remarkable achievement as a reporter and as a writer is taking us inside the hearts and souls of these animals. These are fully drawn characters, with more depth and soul than those cardboard cutouts in an airport paperback mystery.

It’s an unforgettable story. And you will never look at a zoo the same way again.

Tom French writes about animals better than the rest of us will ever write about humans.