Gonzo Without End, Amen

Afterword to Fear and Loathing Worldwide (Bloomsbury Press, 2018)

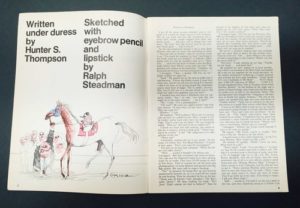

Like artificial sweetener and Post-It Notes, Gonzo Journalism was born of desperation and error. On a foul spring afternoon in 1970, barricaded in a room at the Royalton Hotel on 44th Street in New York, Hunter S. Thompson stared at the paper in the machine before him, wondering what the hell he was going to do.

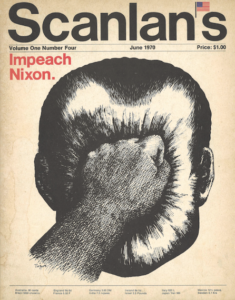

Then came the knock at the door and the arrival of the copy courier, working for the editors down the street in the office of Scanlan’s Monthly. Earlier, Thompson had handed the boy what he’d completed, the first part of his story on the Kentucky Derby. But when the telltale knock came again, Thompson was still staring at empty paper in his wretched typewriter.

To feed the editors, he ripped several sheets of scribbling – on yellow, legal-sized paper – from his notepad, and sent the boy on his way. When the boy left, Thompson sat, finished his cigarette, and began packing for his return home to Colorado. My career is over, he thought. I’ll never work in this business again.

“I was full of grief and shame,” Thompson recalled. “It was the worst hole I’d ever gotten into. I was finished. I was sure it was the last article I was ever going to do for anybody.”

Then came another knock at the door. Please sir, can I have some more? The boy was back. Turns out the editors had liked Thompson’s notes and planned to print them word for word, unedited, in the magazine. So he gave the boy more notes.

“The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” appeared in the magazine the following week. By then, Thompson was back in his fortified compound outside Woody Creek, Colorado, but soon the messages started to arrive. He’d written to his friend Bill Cardoso that he had produced a piece of irresponsible journalism. The letters and phone calls made him think he might’ve short-changed himself. After reading the piece, it was Cardoso who wrote back with the greatest praise. “I don’t know what the fuck you’re doing,” he said, “but you’ve changed everything. It’s totally gonzo.”

“The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” appeared in the magazine the following week. By then, Thompson was back in his fortified compound outside Woody Creek, Colorado, but soon the messages started to arrive. He’d written to his friend Bill Cardoso that he had produced a piece of irresponsible journalism. The letters and phone calls made him think he might’ve short-changed himself. After reading the piece, it was Cardoso who wrote back with the greatest praise. “I don’t know what the fuck you’re doing,” he said, “but you’ve changed everything. It’s totally gonzo.”

Cardoso worked at the Boston Globe and gonzo was local bar slang. It was used to describe the last one standing after a night of heavy drinking. That person, it was recently said, was gonzo.

Others called the piece a breakthrough, the next step in the evolution of journalism. It was both the best and the worst thing to happen to Hunter S. Thompson. “I thought, ‘Holy shit, if I can write like this and get away with it, why should I keep trying to write like the New York Times? It was like falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool full of mermaids.”

It was good because Thompson’s realization that his unedited, unpolished notes made for exciting reading was tremendously liberating for him as a writer. It was bad because it meant that he could publish his unedited, unpolished notes.

From that seed grew the global intellectual industry of gonzo. For its creator, a self-described lazy hillbilly, the persistence of gonzo surprised and amused. Born of laziness, it was another successful effort to see what he could get away with. “Getting away with it” was a dominant theme in his life. The resonance of his work, even after his death, would startle him. The geographic reverberations of his accidental invention would have struck him mute.

This collection shows the remarkable endurance of Thompson’s gonzo approach and its global adaptability. That Boston slang word gets tossed around an awful lot and though aging dilettantes such as myself still prefer the “pure” definition of gonzo (i.e., “whatever Hunter wrote”), it’s time for even us geezers to admit that this thing has become a frothing Godzilla of world literature.

With his ideas in the public domain, it’s no wonder that the Web ethos (“Copyright? We don’t need no stinkin’ copyright!”) has glommed onto gonzo. The democratic nature of the Internet gives a platform to all. Some writers — often the ones who find themselves shut out of commercial outlets — have vented their gonzo spleens in the free-form environs online.

With his ideas in the public domain, it’s no wonder that the Web ethos (“Copyright? We don’t need no stinkin’ copyright!”) has glommed onto gonzo. The democratic nature of the Internet gives a platform to all. Some writers — often the ones who find themselves shut out of commercial outlets — have vented their gonzo spleens in the free-form environs online.

Of course, finding these screeds, no matter how well done, becomes the issue here. More, we have learned, is often less. The world labors under a crush of online commentary, political venting, listicles, clickbait and kitten videos.

That world was alien to Thompson, who never used a personal computer and instead picked away on his IBM Selectric II. (His assistants kept ordering him PCs, but he had no interest; the last one never even got out of the box.) It’s difficult to determine how Thompson would have dealt with the massive amount of information coming at us daily on our smartphones. That device did not exist when he took himself out in 2005. Would he have applauded the sudden cacophony in the marketplace of ideas, or would he have found tedious the self-indulgence propagated by wide-open cyberspace and no editing?

Despite his pop-culture caricature (and his inherent laziness) Thompson was exacting, demanding and often meticulous as a writer. Just as he didn’t suffer drunks gladly (despite his Herculean alcohol consumption), he also held other writers to a high standard. A fierce defender of all of those who rode for the Gonzo brand, he would be unlikely to approve of anyone co-opting his invention and diluting it through either poor work or hastily formed opinions.

Despite his pop-culture caricature (and his inherent laziness) Thompson was exacting, demanding and often meticulous as a writer. Just as he didn’t suffer drunks gladly (despite his Herculean alcohol consumption), he also held other writers to a high standard. A fierce defender of all of those who rode for the Gonzo brand, he would be unlikely to approve of anyone co-opting his invention and diluting it through either poor work or hastily formed opinions.

The style and the attitude born of desperation in that hotel room half a lifetime ago has endured, long after its founder’s death. It’s hard to know how he would regard the work calling itself gonzo today. Can gonzo be self-proclaimed? Is it a starting point or is it a result? He’d likely argue that gonzo was all his and that young writers should stop trying to be him.

Agreed on that point. I’m in my fifth decade of teaching writing. Nearly every semester, by the end of the term, my young writers feel comfortable enough to propose that they write a “gonzo” article.

Go right ahead, I tell them. When they fail, I tell them, See, only one person can write like that, and he’s dead. Pause. But only one person can write like you.

Go right ahead, I tell them. When they fail, I tell them, See, only one person can write like that, and he’s dead. Pause. But only one person can write like you.

Corny, yes. But it makes the point.

As modern America swirls the drain, I’m often asked, “What would Hunter say?” I don’t know; I would not presume to know. He was a complicated man and impossible to predict. But the short answer is this: If Hunter was alive today, he’d kill himself. He was a patriot and an admirer of all of those great handwritten American documents. He could not have lived in the world where the best principles of our nation were fouled upon by buffoons.

Likewise, I don’t know how he would feel about the proliferation of gonzo in this stifling atmosphere of repression and dread. Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe he would want gonzo cut loose, to become egalitarian and set this world on fire. Maybe he would see each new screed as a blow against the empire.

We can only imagine.