Diving Deep Into Dylan

From The Tampa Bay Times, May 7, 2006

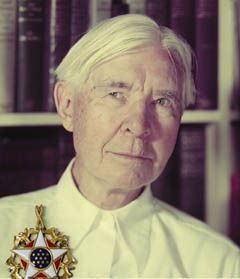

Everyone should see Bob Dylan in concert at least once – for the same reason we should all see the Grand Canyon or Mount Rushmore before we die. Dylan’s a national treasure too, but unlike those monuments of stone, he’s a flesh-and-blood work of American art.

He turns 65 this month, and so the media will be full of tributes. He got tagged with that “voice of his generation” thing about 40 years ago and it has stuck, whether he likes it or not. For some reason, he was the symbol of youth rebellion, or whatever you want to call what happened in the 1960s. When someone who earned a place in history so young hits retirement age, it’s time for pundits to pundit.

But let’s think about this. Dylan wrote “protest” songs back then, but he hated that term. He said they were finger-pointing songs, the way the national anthem is a finger-pointing song. “The Star-Spangled Banner” asks us to question ourselves each time we sing it: Is this still the land of the free and the home of the brave? Dylan also asks questions:

How many deaths will it take till he knows that too many people have died?

He wasn’t trying to destroy anything. He was an embodiment of that American tradition of change. The country is, and always has been, a work in progress, always in the process of rebirth. Dylan knew that change was necessary for survival:

He not busy being born is busy dying.

So many other singers of that time, the ones who did embrace the “protest singer” thing, spoke the “lies that life is black and white” that Dylan denounced. He knew that the self-righteousness of youth is blind to life’s shades of gray, and that the world does not sit still.

I was so much older then; I’m younger than that now.

That was the Dylan of 40 years ago, wise beyond his years. The Dylan of today has endured and remained a vital and active artist. His recent work may be his grandest; it affirms that, like Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and Carl Sandberg, he is a pure product of America.

Dylan’s life has been a great window on his times, from his early acoustic years as the writer of America’s new anthems to his brief, chaotic reign as the king of rock ‘n’ roll. He withdrew from the public to raise a family and embraced country music. In middle age, he turned his eye to searing examinations of the complexity of modern love and shared with us the doubt and faith that infused his revolutionary spiritual music. Finally, he recognized that his art finds its fullest expression not in the recording studio, but on the stage.

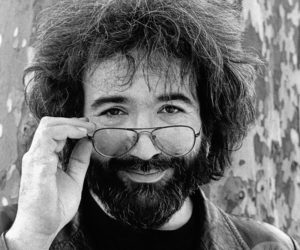

He is the most accessible artist of his stature. His performance schedule would exhaust a singer one-third his age. His epiphany as a performer apparently came in the 1980s when Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead told the sometimes-reclusive Dylan that his songs needed an audience in order to come to life. Garcia taught Dylan to embrace that audience, and so his concerts of the last 20 years — on what he calls his Never-Ending Tour — have been nightly reinventions of his work. He experiments with melodies and lyrics, sometimes rendering his classic songs unrecognizable. But in the process, the songs are made new, for both artist and audience.

It’s important to note that Dylan is an acquired taste. When I was a teenager, my father stuck his head in my room while Blonde on Blonde dripped from my speakers. “That guy can’t sing,” he said after a couple of moments. “You’re right, Dad,” I said. “He can’t sing. But he’s a great singer.” Whenever someone presses me with that he-can’t-sing stuff, I quote that little exchange.

Dylan inspires fierce loyalty from his audience. There are those who follow him on tour, seeing maybe 10 shows in two weeks. I’m not one of those. I’ve seen him a dozen times, dating back to 1974, and I’ve never been disappointed. The dude rocks.

His concerts the last few years have been stunning. His magnificent voice – one critic said it sounded like a broken speaker – still finds unexplored corners in his songs. He remains a fearless detective of the heart, discovering moments lost or put away because they were too honest or too true. A Bob Dylan song, whether written in 1966 or 2006, is a mirror in which we can see what we have the courage to see.

But the “acquired taste” thing – it can test relationships. Over the years, I’ve taken doubting girlfriends, suspicious hip-hop-raised children and disco-bred wives to see Dylan in concert. Usually, about three songs into his set, it hits them, and they learn to love that Bob. Once, my date grabbed my arm and said, “Oh my God – I’m in the same room with Bob Dylan!” It’s like waking up and finding a sequoia in your back yard.

Dylan – with another genius of American music, Merle Haggard – will play the University of South Florida Sun Dome on Wednesday. Don’t miss your chance.