There Used to be Giants

Appeared in Creative Loafing.

I shared air space with Al Satterwhite for about 10 minutes back in the summer of 1974. We were standing in the photo department of the Palm Beach Post. He was on his way out, on to grand and glorious things in California. I was just arriving from a newspaper that had folded up north, long before that kind of thing became fashionable. I was catching up with some of my photographer friends from that paper who had also landed at the Post.

So there was Al, on his way out the door. I said hello, we talked a few minutes and then he was gone. Some of his friends in the photo department didn’t know how he was going to do it, away from the safety net of a newspaper and its regular paychecks. (I know — it was a different era.)

Next thing I knew, his name was attached to those wonderful pictures illustrating the Playboy interview with Hunter S. Thompson in November 1974.

Al did all right. That’s a little like saying that Brando kid did OK in the movies.

Satterwhite’s from Tampa Bay, graduated from Boca Ciega High, and worked for the St. Petersburg Times while still a teenager. He spent a year as Gov. Claude Kirk’s personal photographer (“A fun guy, from my point of view,” Satterwhite says), and did time at some of the country’s finest public universities. “I was skipping around the country, trying out different colleges,” he explains. After a tour of duty in Palm Beach, he headed west. “I was dirt poor,” he says, “but happy to be back shooting real pictures again.”

He’s spent the intervening decades recording the life of California, New York and (lately) Texas. He’s lived a little bit of everywhere (“Been a gypsy,” he says) and done a little bit of everything. He’s been a filmmaker recently, but every now and then he takes a look back on his photojournalism and shares the results with us.

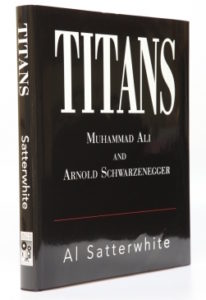

His latest production is a book big enough to be its own coffee table. And that’s appropriate, considering the larger-than-life subjects.

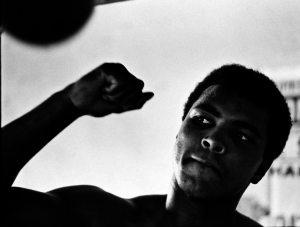

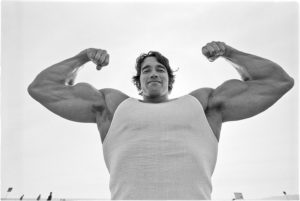

Titans (Dalton Watson Fine Books, $89) showcases Satterwhite’s brilliant black-and-white chronicles of Muhammad Ali and Arnold Schwarzenegger in their prime. Rarely has Ali looked more beautiful, a pure product of America. And here is pre-public-servant Arnold, young and innocent. (OK, at least young.)

Titans (Dalton Watson Fine Books, $89) showcases Satterwhite’s brilliant black-and-white chronicles of Muhammad Ali and Arnold Schwarzenegger in their prime. Rarely has Ali looked more beautiful, a pure product of America. And here is pre-public-servant Arnold, young and innocent. (OK, at least young.)

Satterwhite shot Ali in 1971 during his South Florida days, as Ali prepared for his knockdown dragout with Joe Frazier. He came across a young Arnold five years later, while the future movie star and governor worked out at Gold’s Gym in Southern California, preparing for the film career that all the best minds of his generation figured would never happen.

We learn a lot about these two … well, titans … from these huge images. Today, of course, we have prying cameras that fit on our pinky fingers and we can see just about anyone up close and personal. Read Perez Hilton or any of the other gossip sites, and you can find pictures of celebrities’ nasal hair.

But rarely have you seen pictures as intimate as these images of Ali and Arnold. These photographs reveal their souls. Most of us say we want to take a picture. But all of the great photographers I’ve worked with have always said, as they approach their subjects, “Let’s make a picture.” So with Ali and Arnold, Satterwhite was blessed with great collaborators.

Mostly, Titans makes us nostalgic for the kind of photojournalism that’s sort of hard to find nowadays. I know, we have slideshows and lots of quick-cut dissolving images online. But it’s hard to find pictures this strong that stay with you.

Satterwhite has been in a reflective mood lately. He’s moved on to making films, but every now and then he dives into his archive to assemble another book. Along the way, he made himself into one of the most respected photographers both in news and advertising. His other-worldly art has illustrated campaigns for American Express, Coca Cola, Honda and Universal Pictures. He was dubbed a Nikon Legend, which is the photo equivalent of being knighted by Queen Elizabeth.

So for decades, Satterwhite has been at the top of the photo pyramid in journalism, advertising and film. He’s published technical books (On Colour and Design and Lights, Camera, Advertising) and has taken earlier dives into his archive for Round Pictures and Racing … the Drivers.

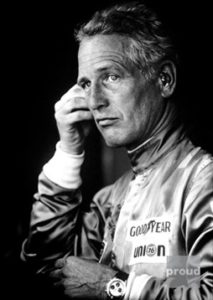

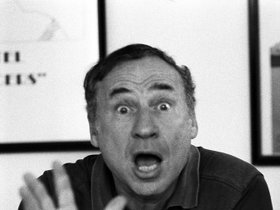

Looking through his online galleries, you can see he’s just begun to tap his files. In addition to his thrilling racing pictures, he’s created a heart-breaking series of life in the South during the ’60s and ’70s. For the celebrity lovers among you, his portraits of actors, musicians and writers are definitive and iconic: Mel Brooks in full-court clown press; Burt Reynolds in his Smokey and the Bandit glory days; John Wayne near the end, and Paul Newman and Steve McQueen in their racing uniforms.

Do people still take pictures like this? If they do, their work is probably buried online in some overwhelmed and hard-to-find Web site in this information-choked culture. A computer screen is static, and so much passes through it that all power is bled from the screen. The technology takes the edge off of everything, and the photos lose much of their power to startle.

“Photojournalism today seems to be in freefall,” Satterwhite says. “Magazines are dropping like flies and nobody does picture stories. Once People got cranking, it all changed. Life was the bible in the ’60s and into the ’70s. Papers like the [Palm Beach] Post ran whole special editions with picture stories on migrant workers. It was amazing. Nobody does that anymore.”

So two of the greatest things about journalism — long works of narrative non-fiction and strong picture stories — are casualties of the new media and a critical-list economy.

“Photography is in perilous times,” Satterwhite says. Still, he has hopes for new media. “I think new media is going to morph into something, and it will be laptops and cell-phone delivery with moving image.” For a moment, he ponders the new equipment and how it’s democratizing the process of photojournalism. “I just don’t know how all these photographers are going to find work. Most aren’t. The cameras have gotten so good, even Ashton Kutcher can shoot pictures ‘like a pro.’ Now that a police reporter can shoot his own pictures instead of sending out an expensive photographer… the good old days are over. The new days are coming. People get ready.”

For now, we look forward to further plunges into Satterwhite’s archive, for another book with the staying power and resilience of Titans.