Humor in the Sacred and Profane

Appeared in the Boston Globe, November 6, 2010

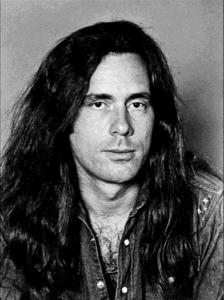

Tom McGuane fit the template perfectly. He lived in Key West, wrote novels about hunting and fishing and drinking and brawling, and sailed out to sea, hoping to catch the big one.

No writer was better positioned to be the New Hemingway than Thomas McGuane in the early 1970s.

McGuane lived that sprawling, Cinemascope life, along the way becoming a legendary boozer and the subject of tabloid fodder. But he avoided the demons that drove Ernest Hemingway to suicide at age 61.

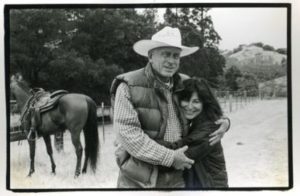

McGuane is 70 now, in his fourth decade of sobriety and in the 32d year of marriage — a significant achievement considering he had three wives in three years back in his tabloid days. He long ago left behind drugs and alcohol and the tropics for an isolated ranch in Montana, where he lives the happy-ending life he so rarely writes about.

As a novelist, McGuane has been prolific. Driving on the Rim, his excellent new book, is his ninth novel. He’s also published two short story collections, three nonfiction books, and five produced screenplays.

But still, despite his considerable literary reputation, McGuane frets that people don’t understand him. The books are funny, so he wonders why more people aren’t laughing.

The confusion is understandable. There’s an awful lot of calamity in these books McGuane calls his comic novels.

Driving on the Rim shows McGuane at his best, expertly quilting together the sacred and the profane, the comic and the tragic.

McGuane tells the story in the voice of Irving Berlin Pickett (his mother named him for the composer of “God Bless America’’ ) and so from the start of his life, the joke appears to be on Berl. He’s born to vagabond rug cleaners who ignore their only child, rather than dote on him.

Berl grows up in Montana and McGuane writes lovingly of the land. Few writers have such a deft touch with language and Driving on the Rim should be read aloud and savored.

At first, living in Big Sky Country seems to matter little to Berl; he might as well be in Iowa. Gradually, he comes to realize that where he lives has defined who he has become.

And he’s become something of a mess. In his life, Berl plays the role of victim.

Berl staggers through adolescence and despite a strong oafish streak, has no trouble with women. His roguish aunt seduces him. The bawdy girl upstairs in his boarding house throws herself at him. The wife of an older gentleman latches on to him like a junebug on a willow branch.

All of these affairs end badly, but Berl perseveres and through dumb luck becomes the protegé of a local doctor. His parents provide him with prayer and nothing else. The local doctor takes him hunting and fishing and teaches him to love the land. Then, absent a child of his own, he supports Berl through medical school, though it’s not clear the young man is a good investment.

Up to this point in the book, the comedy is on sure footing. Even the disclaimer before the first chapter is funny.

But as the misfortunes accumulate, Berl’s life begins to unravel and the world goes mad. Tragedy threatens to strangle him and his good spirit. He finds solitude and healing in the wilderness, but even that idyll is ruined when news of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, finds him in a remote corner of the world. Nowhere, it seems, is he safe from life.

So maybe that’s the comic touch McGuane says people miss in his novels. No matter what we do, we can’t escape mortality. The joke’s on us.