A Space Filled with Moving

Appeared in the Tampa Bay Times

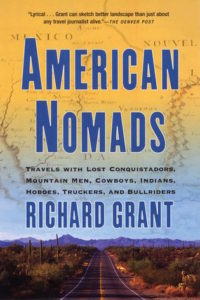

Gertrude Stein nailed us when she said America was “a space filled with moving.” We’re restless people and no matter how far interest rates fall, some of us will never feel at home in a home.

Halfway through American Nomads, Richard Grant’s book on our wandering culture, we meet a guy named Lance Grabowski. He’s been drifting through the West for 30 years with no permanent home, no family, no woman for more than a few weeks at a time – and he is, of course, happier than a pig in slop. Looking back on this life, he tells Grant: “The truck was my armchair and the country was my house. The different parts of the country were like different rooms in my house: ‘Oh, it’s October, the fall colors will be coming out in upstate New York.’”

It isn’t that Lance hasn’t tried living like the rest of us, with mortgages, car notes and irritating neighbors. He’s just not cut out for a subdivision. So he wears buckskin, totes primitive weapons and lives out of his truck, selling hand-made jewelry and bleached buffalo skulls on the swap-meet circuit. He doesn’t understand why more women don’t want to live in vans and tents and he thinks the feminist movement is a plot to make life difficult for free-spirits like him.

Lance isn’t an isolated case. Richard Grant has found a culture of full-time wanderers, most of them in the great expanse of American West. Some – like long-haul truckers and carnies – do so by trade. Others are wanderers by inclination. Like Lance, they don’t do the nine-to-five. These are people who don’t own anything they can’t fit into a backpack, who look at finding the next meal as a contact sport, and who understand that a campfire isn’t just a source of light and heat, but a thing of wonder and beauty.

Sometimes it takes an outsider to see what’s inside us. Like fellow Brits Jonathan Raban and (for an earlier generation) Alistair Cooke, Grant has a greater appreciation for things American than most of us do. He loves our culture and history. Perhaps it’s European envy for the yawning American horizon. “Open space invites mobility,” Grant writes. He throws himself in with the itinerant culture, confessing that staying longer than a few days in his Tucson rental gives him the willies.

It would be great to travel with Richard Grant but if American Nomads has a fault, it’s the lack of a strong narrative velocity. He doesn’t unfurl his stories and introduce us to his fellow road warriors while we ride shotgun in his pickup. We don’t really get the sense that we’re on the road with him and we miss that kind of literary intimacy. We’re just thrown in with his memories and our nation’s jumbled history.

But that’s a quibble. Grant is a great storyteller and he shifts through several centuries as he chronicles the lives of American nomads.

He counters the modern-day stories (buckskinners like Lance as well as truckers , festival-hopping weekend hippies and other nomads) with frequent plunges into history with mountain men, religious pilgrims and lost conquistadors.

Grant has a special fondness for a 19th Century fur trapper named Joe Walker, whose life on the road debunked the notion that the root of American rootlessness was a desire to get rich. For Walker, travel wasn’t the means to an end; it was a worthy end all on its own.

The Mormons were America’s foremost religious pilgrims in the 19th Century and several of them, perhaps dazed from too much time baking in the desert sun, concocted theories that Jesus Christ was the quintessential American nomad, arriving as he did via wooden submarine during an extended vacation from the Holy Land.

Then there’s the tale of Cabeza de Vaca, who wandered – naked, mostly – through the Southwest, a displaced 16th century Spanish explorer whose travels included stints living with Indian tribes, subsisting on grubs and berries and developing a disdain for the sedentary (and supposedly civilized) life he’d led for his first 40 years on earth. Events turned him into a vagabond and he was never able to return to his old way of life.

Nomadism is a way of life, but perhaps not a life sentence. After years of curled-up sleep across a front seat, Grant admits that he fell off the wagon. Owing to a fear of deportation and the love of a long-suffering woman, he finally wed and began to put down those roots he’d heard so much about. This last-page admission gives American Nomads what we can only assume is a happy ending.